Blockchain Attacks

Blockchains are generally considered to be very secure, but the level of security they provide is proportional to the amount of hash power that supports the network.

The more miners there are and the more powerful their mining hardware is, the harder it is to perform an attack on the network.

In this article, we review some of the most common attack scenarios on public blockchains, how they occur, and how they're addressed.

The Byzantine Generals Problem

Before we get into the different attack scenarios we would like to introduce you to a sort of thought experiment, namely the Byzantine General's Problem that remained unsolved for centuries until blockchain technology was introduced.

Imagine you are a general a few centuries ago and you want to attack a castle with your army.

The castle is very robust and the army inside is strong. You have arranged a number of other armies to support the attack and each of those armies is going to attack from a different side. The armies are separated by distance, each of them several miles apart.

If they all attack at the same time the chances of victory are very high. If the attack is uncoordinated then they will most likely suffer defeat.

You as the general have the following problem:

How can you make sure all armies are attacking at the same time? In other terms, how can you achieve consensus on the time of the attack?

You cannot give signals with flags, torches or smoke, as those signals could be picked up by the enemy.

You could send messengers on horseback, but what if one of them is captured or killed before he reaches the intended General?

To know the other generals received the message, you could have them send a messenger back with a confirmation. The messengers carrying the confirmation could be captured or killed as well on their way back to you.

The other generals wouldn't know if you received their confirmation, so you would have to send out confirmations of the confirmations but what if those messengers get captured?

Even without the risk of imposters transferring fraudulent messages and traitors confirming to attack with the intent of not doing it this situation was thought to be impossible to solve. Nobody could know with absolute certainty if the other generals intended to attack at the same time or not.

Blockchain technology solved this dilemma - although this would not really have helped the Byzantine army.

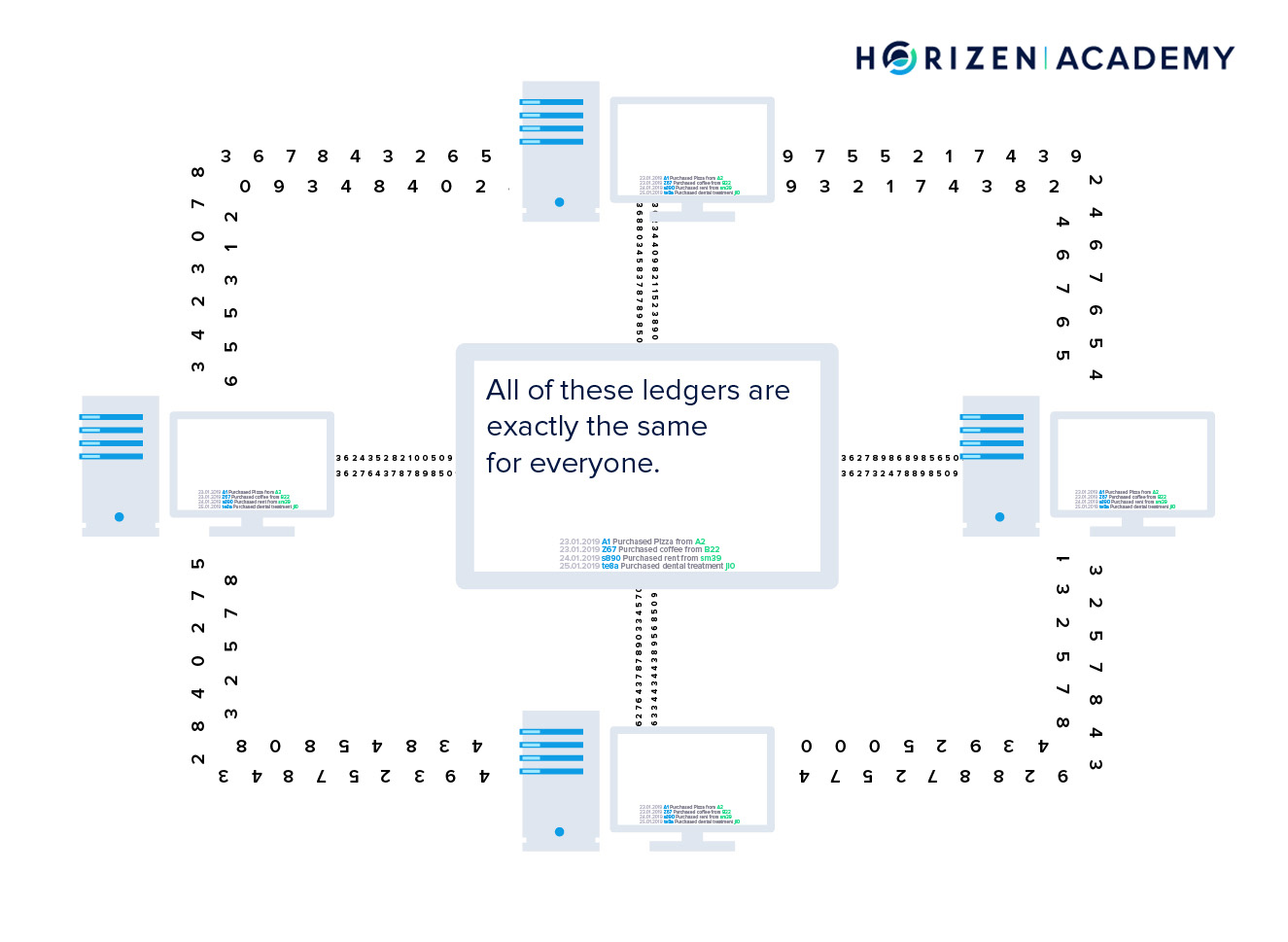

Each General now has a ledger of events that is synchronized with the other General's ledgers. No central party is in charge of the coordination. Every time a block gets mined, all the participants agree on the order of events for the last couple of minutes.

Getting back to our general's problem, now they have a way of knowing if all of them are going to attack, or if they should retread collectively.

Now that we have talked about the general problem a consensus mechanism aims to solve, let's look at some simple and intuitive attack scenarios and how we address them.

51% Attack

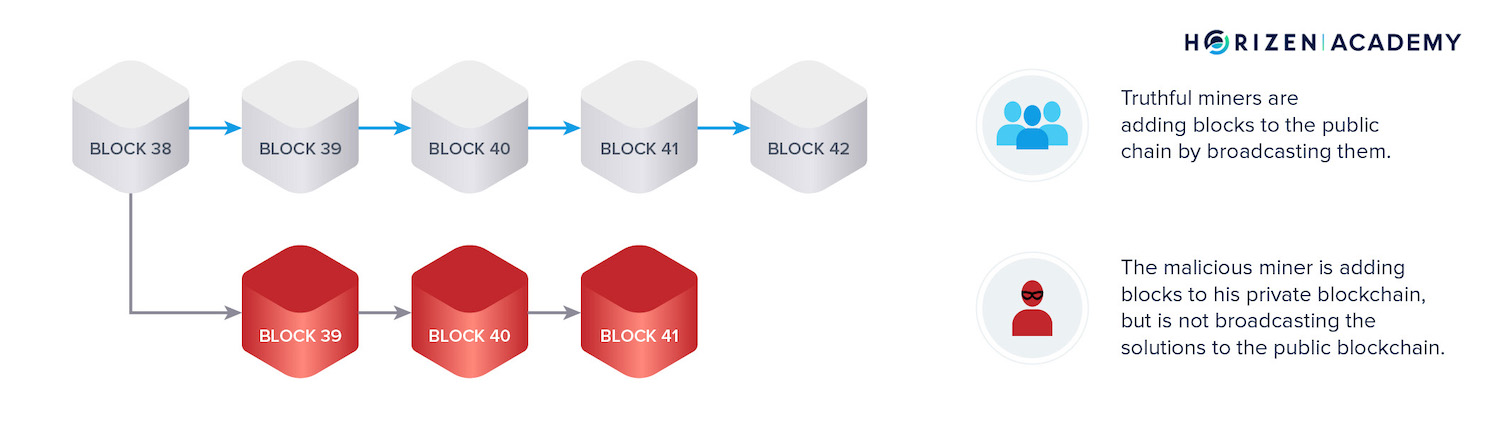

The best-known type of attack on public PoW blockchains is the 51% attack.

The goal of a 51% attack is to perform a double spend, which means spending the same UTXO twice. To perform a 51% attack on a blockchain, you need to control a majority of the hash rate, hence the name.

A malicious miner wanting to perform a double spend will first create a regular transaction spending their coins for either a good or for a different currency on an exchange. At the same time, they will begin mining a private chain.

This means they will follow the usual mining protocol, but with two exceptions:

- First, they will not include their own transaction spending their coins in their privately mined chain.

- Second, they will not broadcast the blocks they find to the network, therefore we call it the private chain.

If they control a majority of the computing power, their chain will grow faster than the honest chain.

The Longest Chain Rule in PoW blockchains governs what happens in case of such a fork. The branch that has more blocks to it and accordingly represents the chain created with a larger amount of computing power is considered the valid chain.

Once the attacker has received the good or other currency bought with their coins, they will broadcast the private branch to the entire network. All honest miners will drop the honest branch and start mining on top of the malicious chain.

The network treats the attacker's transaction as if it never happened because the attacker did not include it in his malicious chain. The attacker is still in control of their funds and can now spend them again.

This has happened to many smaller blockchains in the past.

In fact, Horizen suffered from a 51% attack in early June 2018. We immediately started to work on a solution to mitigate the risk of a 51% attack on smaller blockchains that are not secured by as much computing power as for example the Bitcoin blockchain.

We came up with a solution that penalizes delayed block submissions. There is no legitimate reason for a miner to broadcast several blocks to the network at once.

Our protection mechanism makes these attacks very costly.

So costly that it does not make any economic sense to perform such an attack on our network. Many other blockchains are now looking to implement a simamnilar protection mechanism with their protocol.

Sybil Attack

A Sybil Attack is an attempt to manipulate a P2P network by creating multiple fake identities. To the observer, these different identities look like regular users, but behind the scenes, a single entity controls all these fake entities at once.

This type of attack is important to consider especially when you think about online voting. Another area where we are seeing Sybil attacks is in social networks where fake accounts can influence the public discussion.

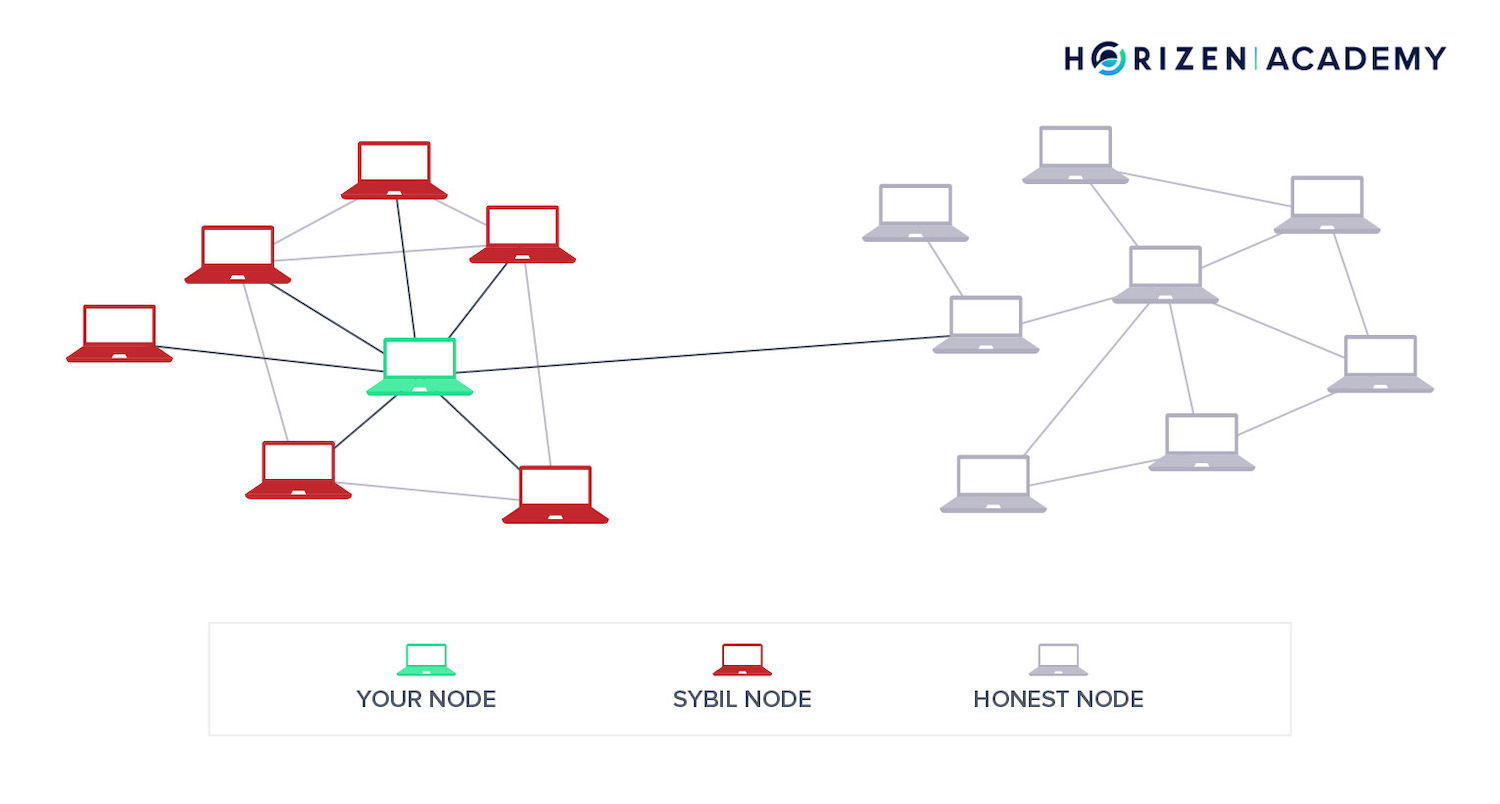

Another possible use for Sybil attacks is to censor certain participants.

A number of Sybil nodes can surround your node and prevent it from connecting to other, honest nodes on the network. This way one could try to prevent you from either sending or receiving information to the network.

This "use case" of a Sybil attack is also called Eclipse Attack.

One way to mitigate Sybil attacks is to introduce or raise the cost to create an identity.

This cost must be carefully balanced. It has to be low enough so that new participants aren't restricted from joining the network and creating legitimate identities. It must also be high enough that creating a large number of identities in a short period of time becomes very expensive.

In PoW blockchains, the nodes that actually make decisions on transactions are the mining nodes. There is a real-world cost, namely buying the mining hardware and consuming electricity, associated with creating a fake "mining-identity".

Additionally, having a large number of mining nodes still doesn't suffice to influence the network meaningfully. To do that you would also need large amounts of computational power.

The associated costs make it hard to Sybil attack Proof-of-Work blockchains.

DDOS Attack

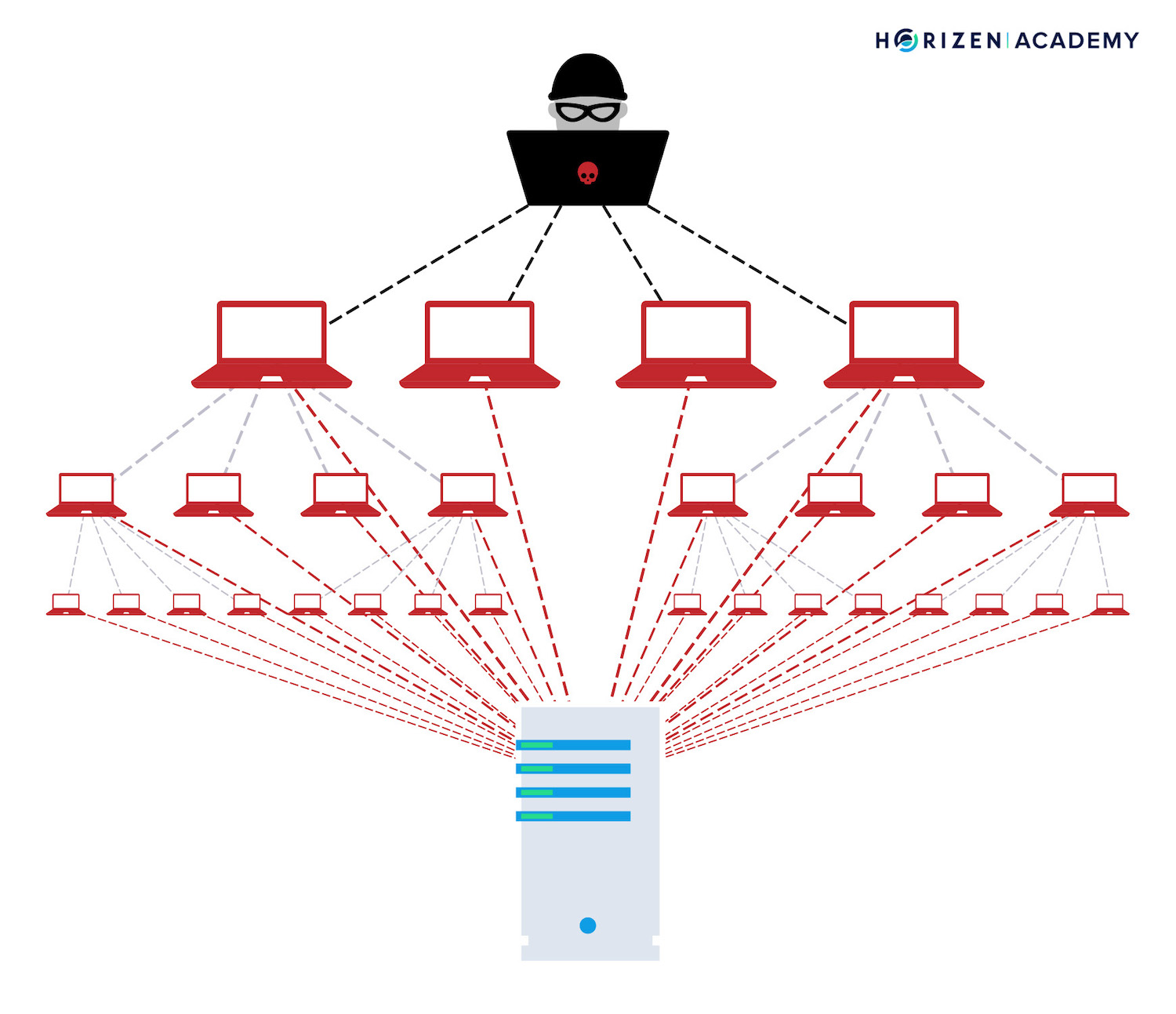

A Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDOS) attack in computing is an attack, where a perpetrator seeks to make a network resource unavailable to its users, by flooding the network with a large number of requests in an attempt to overload the system.

It is an attack that not only blockchains but any online service can suffer from.

In a simple form, the DOS (Denial-of-Service) attack, all these requests originate from the same source. This makes it somewhat easy to prevent.

If a single IP-address sends a huge amount of requests that cannot be justified by legitimate reasons, you can have a measure in place that automatically blocks this IP-address.

In the case of a DDOS attack, the distributed part refers to a large number of different sources that the malicious requests originate from.

A DDOS attack is much harder to tackle because to do so you need to differentiate between legitimate and malicious requests. This is a very hard problem. In the context of blockchains, this comes down to an almost ideological question.

The motivation to introduce transaction fees was to eliminate spam. Some people argue that as long as the requests have a transaction fee attached they cannot be considered spam by definition.

While there are certainly situations where you could consider transactions to be spammy, it would be a slippery slope to start blocking them. One of the greatest value propositions of public blockchains is their censorship resistance.

Starting to pick transactions that are not included - no matter what criteria this censorship is based on - would be a dangerous precedent for any blockchain.

Summary - Blockchain Attacks

Blockchains have solved the Byzantine General's Problem of achieving consensus on the order of events in an untrustworthy environment. There are different ways a blockchain can be attacked. Performing these attacks becomes more difficult over time as more computing power is added to the network and it becomes more robust.

In a 51% Attack, a miner controlling the majority of computing power on the network tries to spend coins twice, by writing a private version of the blockchain first, before broadcasting all blocks at once to the honest miners.

In a Sybil Attack, a malicious actor controls many fake identities and tries to either meddle with online elections or to manipulate the communication in a P2P network.

In a DDOS Attack, a perpetrator wants to slow down or halt the network by spamming it with a large number of transactions.

The attack scenarios presented in this article, except for the 51% attack, are not endemic to blockchains and have been around since the beginning of distributed peer networks. There are many measures in place to mitigate the risk of the different attack scenarios out there.

Blockchain technology is highly secure, but as with anything else in the digital realm, there are no invincible protocols.