Modular vs Monolithic Blockchains

At its core, a blockchain is a social and technological experiment that seeks to identify the best way to coordinate large groups of autonomous individuals (represented as computers) to achieve rapid consensus on highly consequential decisions about the nature of truth in the digital realm.

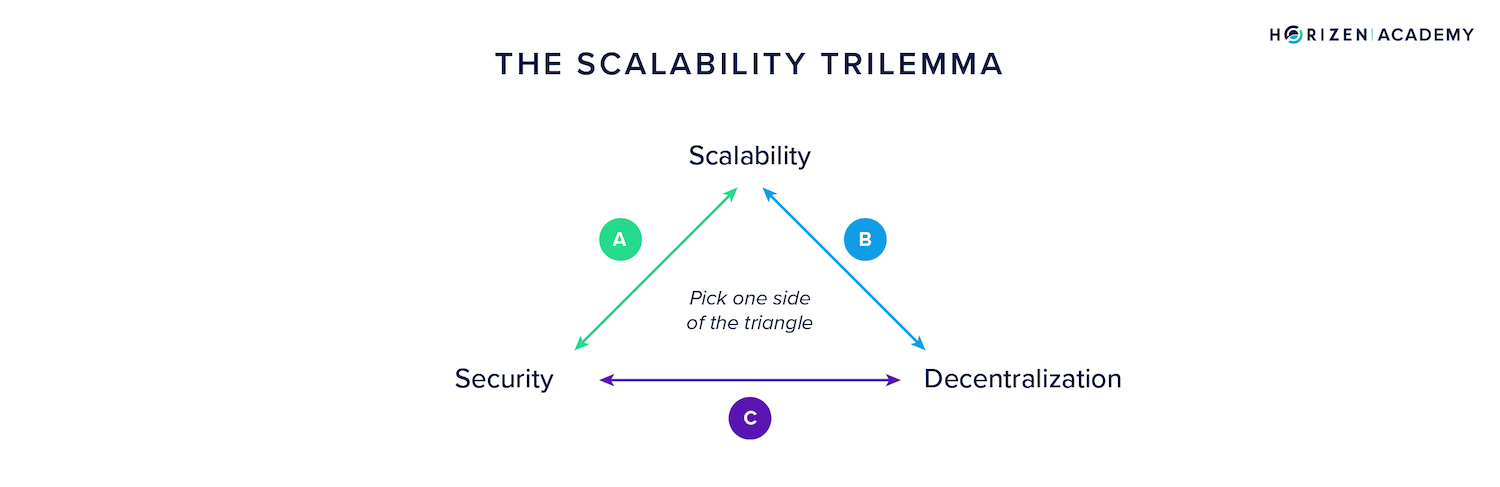

The main challenge associated with this coordination experiment is called the scalability trilemma.

It is impossible to truly understand where we are in the evolution of blockchain technology without first exploring the roots of this trilemma and the unique approaches developers are taking to solve it.

The Scalability Trilemma

The scalability trilemma is a series of trade-offs between decentralization, speed/scalability, and security that one must make when designing a blockchain and constructing rules for its on-chain governance.

- Centralization = Increased Speed, Decreased Security & Censorship Resistance

- Decentralization = Decreased Speed, Increased Security & Censorship Resistance

In theory, it is impossible to achieve perfect decentralization without compromising scalability, and vice versa.

Over the past 5 years, we have seen a slew of new blockchains emerge with the sole objective of trying to manage this tradeoff with a bias towards scalability.

Why Scalability?

Blockchains like any network-driven business require commercial viability in order to attain growth and establish network effects.

In order for commercially viable applications such as DEX’s, P2E games or NFT marketplaces to exist, users must be able to transact as quickly and cheaply as they are used to doing on Web2 applications.

The launch of Ethereum and subsequent competitors have all been an attempt to improve blockchain scalability.

Projects like Binance Smart Chain and Solana are tackling this problem by creating blockchains with larger block sizes, fewer nodes, or consensus mechanisms that require less participation amongst all nodes in order to come to agreement on the state of the network.

Unfortunately, chasing the carrot of scalability and commercial viability comes at the cost of decentralization and, therefore, security.

Once you limit the number of nodes required to validate transactions on a blockchain, you introduce more obvious central points of failure, which can create vulnerabilities for the entire network.

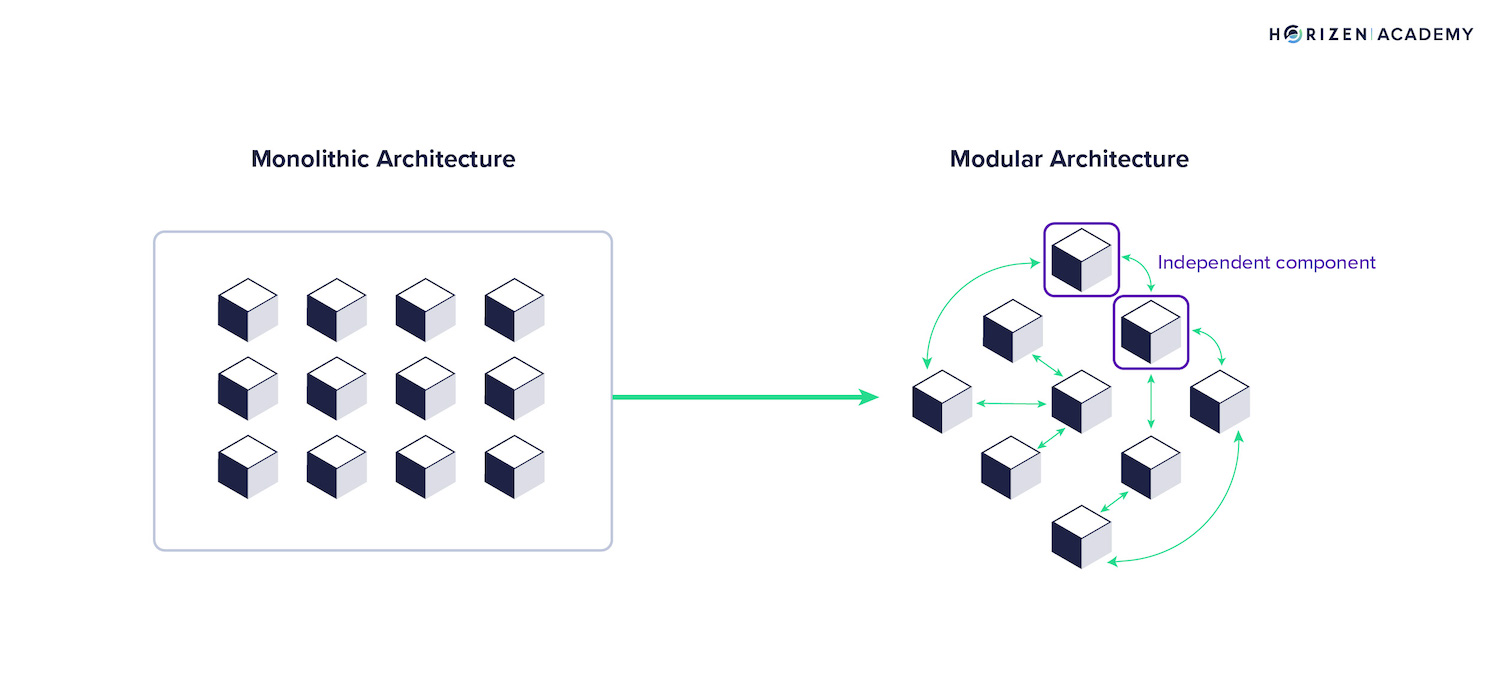

The problem with these attempts to tackle the scalability trilemma is that they are done through a monolithic approach rather than a modular one.

In this piece, we break down what this means and how blockchains like Cosmos, Horizen, and Ethereum 2,0 are pushing the industry forward by implementing modular blockchain architectures.

Blockchain Architectures

The monolithic vs modular framework was recently referenced in an episode of the popular blockchain research podcast Bankless.

In this episode, hosts David Hoffman and Ryan Sean Adams describe the modular vs. monolithic blockchain framework and what it means for the evolution of blockchains.

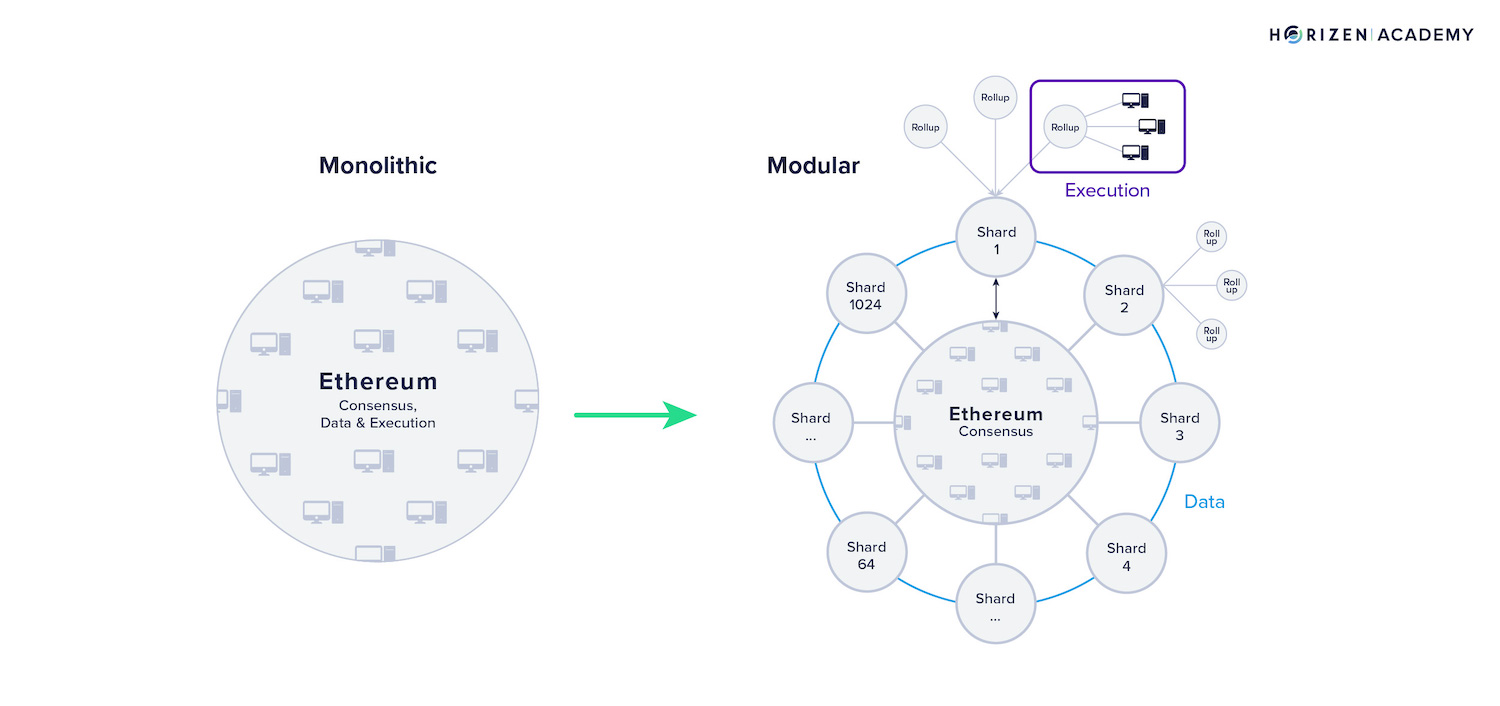

A monolithic blockchain is one in which transaction execution, network consensus (the ordering and confirming of transactions by nodes) and data availability (the ability to verify that all the data from new blocks has been published are all achieved on the same network.

This design describes the vast majority of blockchains, from Bitcoin and Ethereum to Solana and others.

In a modular blockchain, the data availability function can be split up between multiple chains through a process called sharding, which allows nodes to divide up the number of transactions that they need to verify to ensure that all the correct data for each block is published.

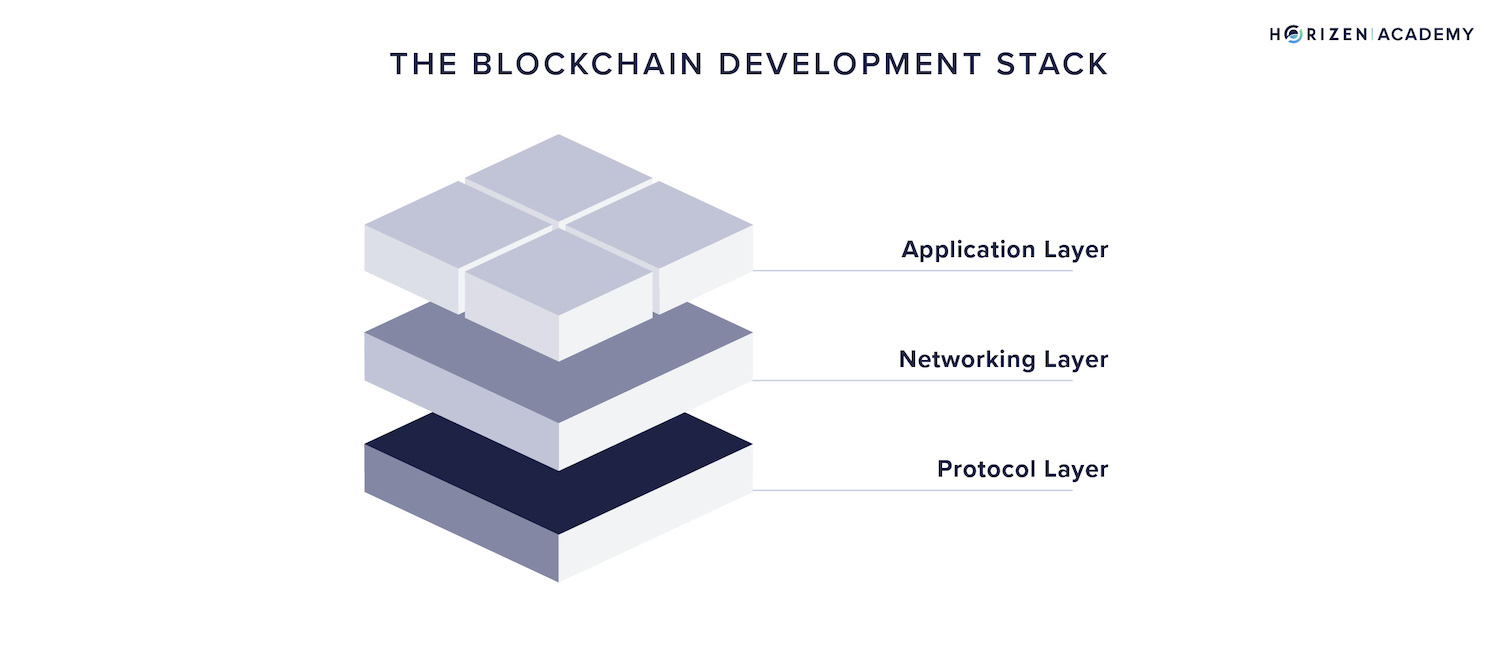

The Basic Architecture of a Blockchain Consists of 3 Primary Layers

- The application/execution layer - where transactions are executed

- The network/consensus layer - where consensus is achieved on what transactions are true and what order they should be arranged in. Consensus and network layers are technically separate, but highly interconnected.

- The protocol/data layer - where the history of validated transactions are stored and can easily be audited

Each layer represents one component in a sequence of downstream events that encapsulate all activities within a blockchain network.

The problem with this monolithic design is that in the absence of specialization, blockchains must make compromises in one or more of their layers in order to achieve scale.

Monolithic Design

To better understand the problems of a monolithic design, let’s use the analogy of a car manufacturer.

A typical car manufacturing company like Toyota does not produce every single part of the vehicle in one facility.

Rather, different parts from the engine to the tires and the steering wheel are manufactured in separate locations where specialized teams can design them before shipping the parts over to a central facility where they are assembled to form the car.

If all parts were manufactured in a single facility, the facility would not only have to be massive, it would also incur significant costs to maintain its infrastructure and pay staff to perform multiple tasks.

The lack of specialization amongst teams would lead to lower quality outcomes, and in the event that there was an increase in car orders, the facility would not be able to scale to meet this demand because of a lack of space or manpower.

This problem broadly describes the difference between modular vs. monolithic architectures.

Ethereum is a monolithic blockchain optimized for decentralization.

It prioritizes the consensus and data layers over the execution layer, which is why it can only process 15 transactions per second, with gas fees reaching as high as $200 per transaction during times of network congestion.

On the opposite end of the scalability spectrum, Solana is a monolithic blockchain optimized for speed.

By choosing to prioritize the execution layer, it can process over 2,000 transactions per second at an average cost of $0.00025.

The tradeoff for Solana is decentralization and a suboptimal consensus and data layer, which is why it has experienced incidents where the entire network shuts down for several hours.

Modular Design

When a modular process is applied to manufacturing cars, tasks are broken up into smaller components and handled by specialized teams, the engine design team, the car body team, etc..

Similarly, with blockchains, a modular architecture is one in which the main responsibilities of transaction execution, consensus, and data storage are broken up and delegated to a network of independent blockchains (sidechains) or layer 2 (L2) channels.

Each sidechain or L2 is designed to make up for the tradeoffs taken by the main blockchain, known as the mainchain). An L2 or sidechain will typically be optimized for transaction execution, enabling faster transactions by leveraging a smaller network of nodes.

The mainchain as the most secure and decentralized network acts as a settlement layer where final consensus is reached on the state of operations within the sidechains/L2s (i.e., what is true).

The storage of validated transaction data can either be done on the mainchain or across different sidechains. This allows the network to alleviate congestion and increase data storage capacity by dispersing transactions across a larger set of nodes.

This is called increasing transaction throughput.

Differences Between L2s and Sidechains

L2s are considered off-chain scaling solutions for blockchains and Dapps, typically set up as payment channels to exchange funds between a small group of participants using a smart contract.

L2’s can exist as simple payment channels, like Lightning Network, or as an entirely separate node network, like Polygon.

What makes an L2 distinct is that it relies on a mainchain network like Ethereum or Bitcoin for final transaction settlement and security.

By contrast, Sidechains are independent blockchains that can operate their own consensus mechanism and can validate and settle transactions independently without the need for a mainchain.

This however does not mean that transactions on a sidechain cannot also be validated by its mainchain, it is just not a requirement for the security of the network to be maintained.

By enabling sidechains and L2s to communicate and transfer value between each other and between the mainchain (a process known as interoperability), a network of blockchains could perform and operate as 1 single blockchain, having solved the scalability trilemma through specialization as opposed to making tradeoffs.

Additionally, with a modular architecture, increased specialization means that sidechains can be optimized for specific traits like speed, security, privacy, and decentralization, instead of all of those traits being forced into one single blockchain with less effective results.

Different Approaches to Blockchain Modularization

While blockchain modularization seems like the obvious approach to solving the scalability trilemma, it can come with its own share of challenges.

One of the main challenges of modularizing a blockchain is that it can take a long time to build the right infrastructure that supports the development of independent, yet interoperable sidechain networks.

The key questions to answer when designing a modular blockchain network include the following:

- What is the relationship between the various components (mainchain, sidechains, Layer 2s) that make up the modular network?

- What is the mainchain compensating for by connecting with a sidechain or L2, and what is the sidechain or L2 compensating for by connecting with a mainchain.

- What is the transfer process between the mainchain and the sidechain or L2, or between different sidechains and L2s?

- How does this modular architecture improve the overall performance and decentralization of the network?

- Is it truly solving the scalability trilemma , or are there still trade-offs being made?

Based on these questions, let’s compare how various projects are approaching blockchain modularization:

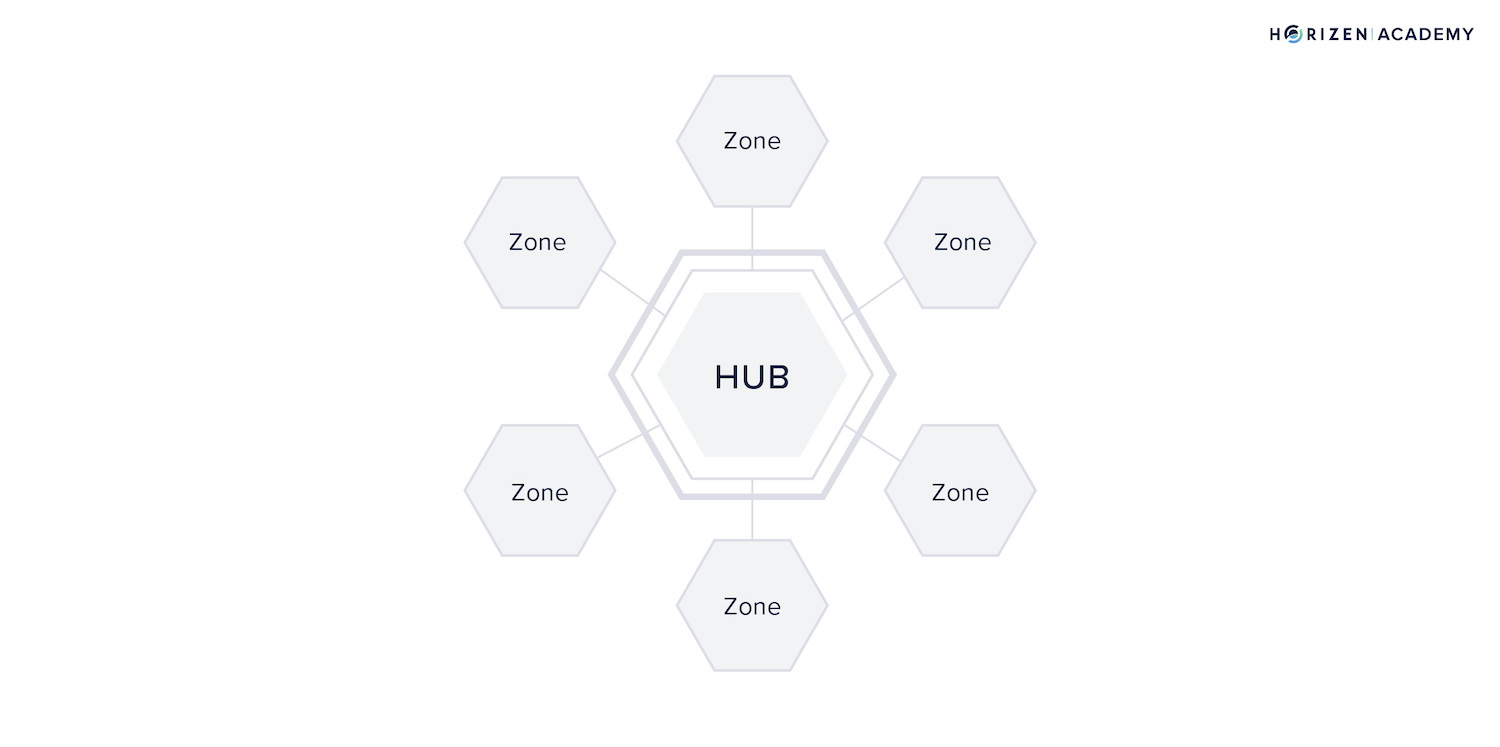

Cosmos

- Sidechain = Zones

- Mainchain = Hub

- Interoperability Mechanism = Inter-Blockchain Communication protocol or IBC

Cosmos is one of the most popular examples of modular blockchain architecture.

It hosts about 262 Dapps and blockchains, including Binance Smart Chain and the Terra blockchain.

Cosmos is a scalable and interoperable network of blockchains, commonly referred to as the ‘internet of blockchains’. Using the Cosmos SDK, developers can launch their own PoS blockchains, or ‘Zones’.

Cosmos Zones are connected by a central blockchain network called the Hub. Hubs receive a stream of block-commits from Zones, which allows them to keep up with the state of each Zone.

Using a mechanism called the Inter-Blockchain Communication protocol (IBC), Zones can communicate and transfer value between each other using the HUB as a central checkpoint and intermediary.

The Cosmos Hub is secured by 125 validators using PoS. ATOM tokens are earned for validating transactions on the Hub.

Zones are independent blockchains and can therefore have as many or as few validator nodes as desired. In addition, the security of a Zone is strictly managed by the nodes on the Zone and there is no reliance on the mainchain Hub.

Cosmos is commonly referred to as a layer 0 protocol. Layer 0’s enable developers to launch multiple layer 1 blockchains/sidechains that can be designed to serve a specific purpose and cater to 1 or 2 dimensions of the scalability trilemma as opposed to all 3.

Through interoperability features, these L1 networks can also be made to communicate with each other such that the end-user can have the experience of using one blockchain while they are, in fact, using multiple.

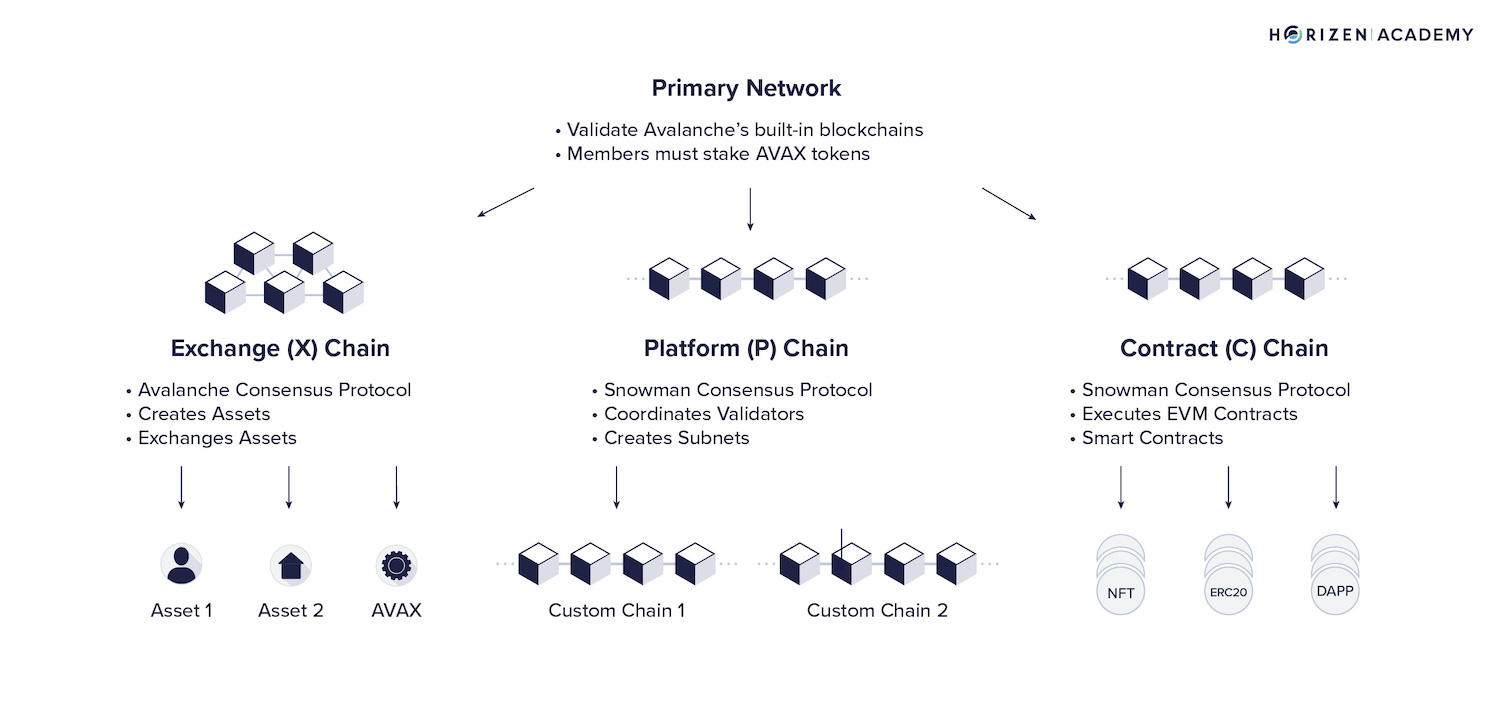

Avalanche

- Sidechains = Blockchains validated by Subnets - a dynamic set of validators that validate transactions on a blockchain

- Mainchain = Primary Network - a special subnet that validates the entire Avalanche network

- Interoperability Mechanism = Cross-Chain Bridges

Avalanche is a more recent entrant into the modular architecture space.

Rather than a simple mainchain and sidechain structure, the Avalanche network is broken up into four components that are each optimized for a specific purpose:

- Primary Network - A special subnet responsible for validating Avalanches 3 blockchains (X-Chain, C-Chain, and P-Chain). Becoming a member of the primary network required staking Avalanches native token AVAX.

- Exchange Chain (X-Chain) - Designed for creating, managing, and transacting tokens on the Avalanche network

- Platform Chain (P-Chain) - Designed for managing subnets and coordinating validator nodes and the staking mechanism

- Contract Chain (C-Chain) - Designed for creating smart contracts using an instance of the Ethereum virtual machine (EVM) - enables developers to deploy Ethereum Dapps to the Avalanche ecosystem

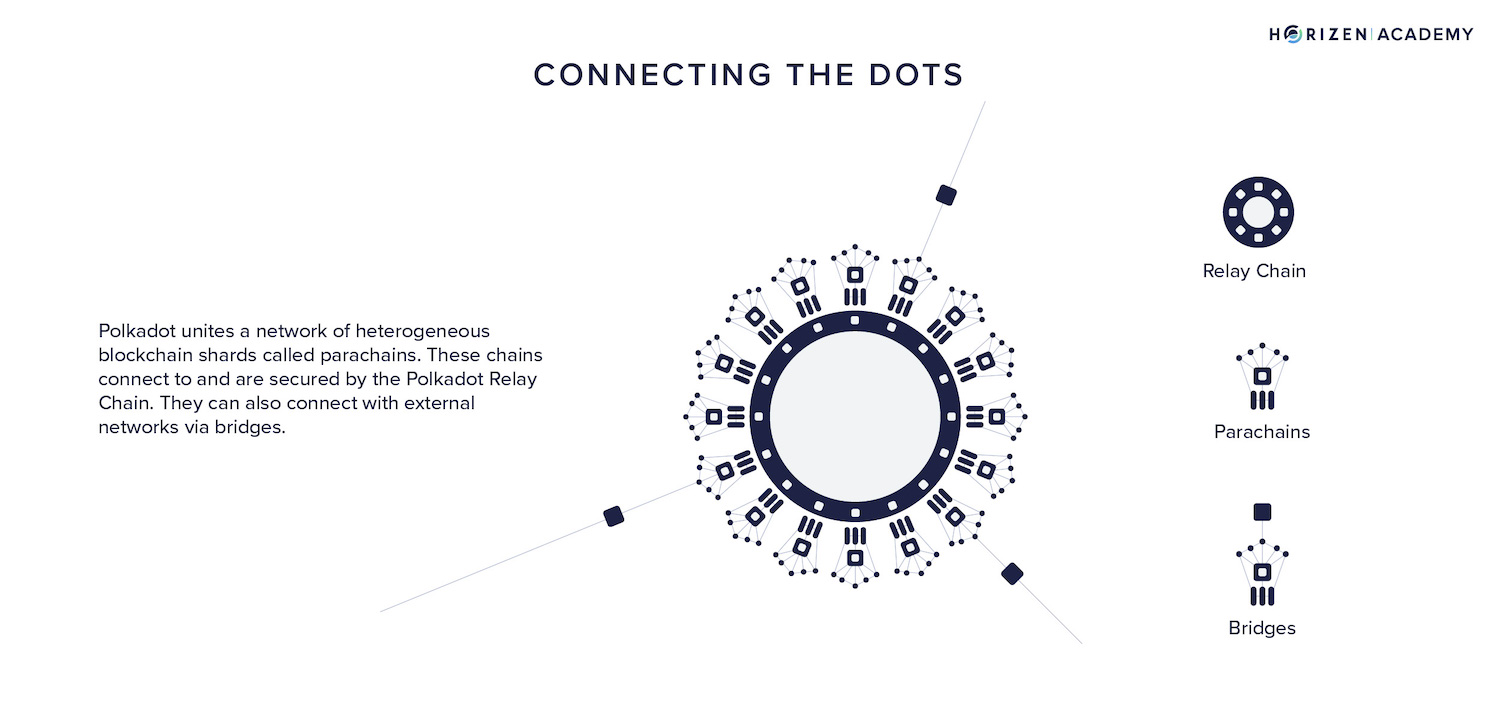

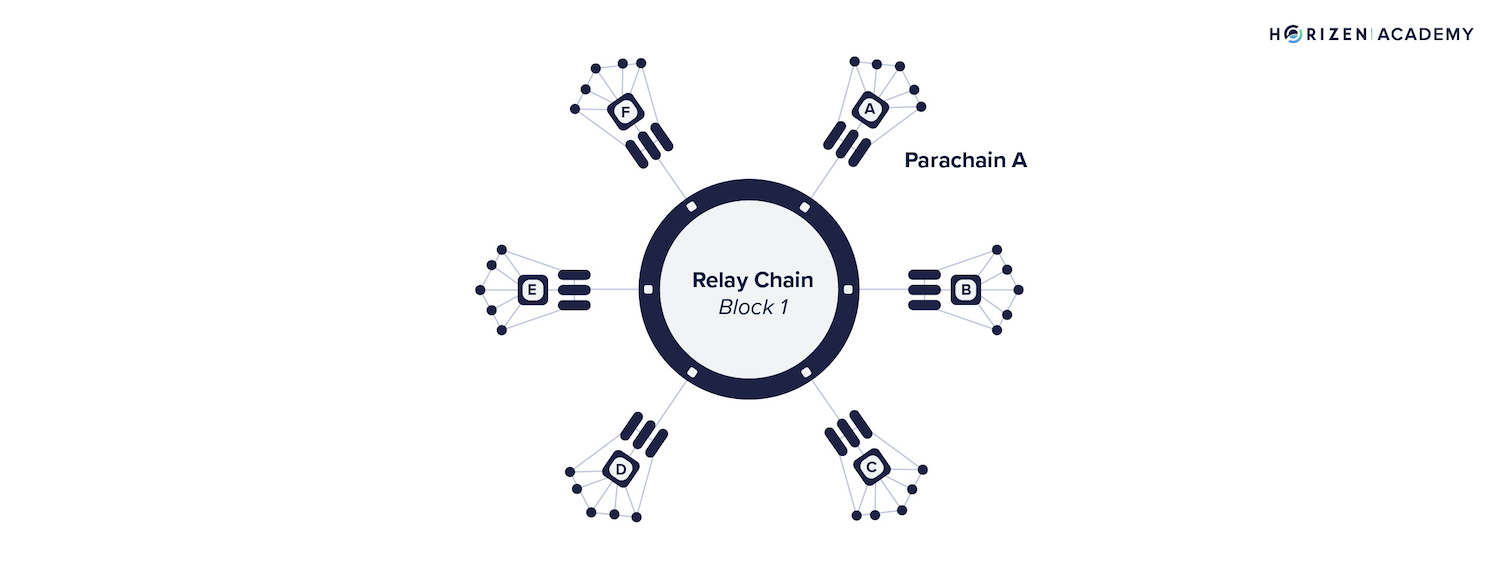

Polkadot

- Sidechain = Parachains

- Mainchain = Relay Chain

- Interoperability Mechanism = Bridges

Polkadot is a blockchain protocol that unites an entire network of purpose-built blockchains known as ‘parachains’.

Parachains are connected and secured by the Polkadot Relay Chain. They can also connect with external networks via bridges.

Additionally, Polkadot’s network provides a shared security model between parachains, meaning that the Relay chain validators are responsible for validating transactions of all parachains on the network and securing them through their staked DOT tokens.

This shared security model means that parachain developers do not have to worry about attracting enough miners or validators to secure their own chains.

Under the shared security model, parachains function like an L2 in that they rely on a mainchain (the Relay chain) for final transaction settlement and security.

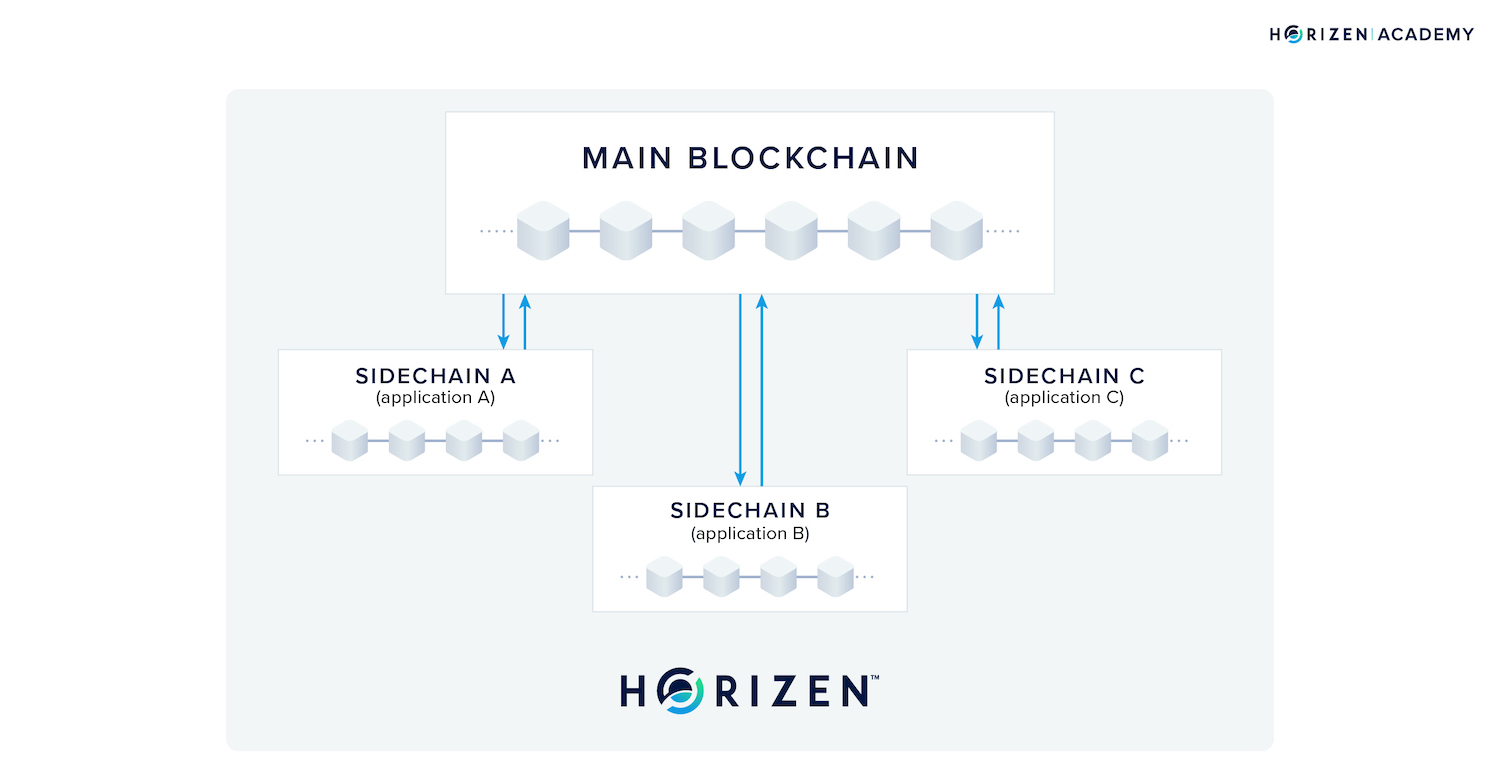

Horizen

- Sidechain = Sidechains

- Mainchain = Horizen Network

- Interoperability Mechanism = Cross-chain transfer protocol

- Sidechain Protocol: Zendoo

Horizen is building a network of independent blockchains, sidechains, that connect to a proof of work mainchain.

Horizen’s unique differentiators include its emphasis on privacy-preserving technologies like zk-SNARK and its highly secure proof-of-work mainchain.

Horizen uses zk-SNARKs, Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge, to enable transactions that occur on its sidechains to be verified on the Horizen mainchain without the nodes knowing the sidechain transaction data being validated.

Mainchain nodes on Horizen do not need to validate sidechain transactions using PoW. Instead, using zk-SNARKs, the nodes only need to verify ‘proof of computation’ for virtually any number of sidechain transactions that have occurred on the network.

This reduces the computational load of the mainchain and further helps to enhance the network's overall scalability capabilities.

As we have seen from the three previous examples, the common design amongst modular blockchains is a decoupled and neutral mainchain (or set of mainchains) that serves as a checkpoint on the state of sidechains as an intermediary between sidechains, or as a final settlement layer for L2s.

To perform these functions, the mainchains need to serve as the definitive point of truth.

To achieve this, a mainchain needs to be highly secure, which is why Horizen is the only modular network that has chosen to stick with PoW and has actually designed a more secure version of the PoW consensus mechanism; leveraging a ‘penalty system for delayed block submission’ to enhance protection against 51% attacks.

The Horizen mainchain also consists of over 35,000 nodes, making it the largest node network in the Web3 space.

Additionally, to attract more developers to build sidechains and L2s on a modular blockchain network, the mainchain must also be privacy-preserving.

This gives traditional companies the flexibility to leverage public blockchain network security while retaining the privacy of their transaction data on a permissioned sidechain network.

These distinctions make Horizen one of the most flexible modular blockchain networks available today.

Ethereum 2.0

- Sidechain = Shards/Shard Chains

- Mainchain = Ethereum Mainnet (soon to be the Beacon Chain)

- Interoperability Mechanism = Bridges, Optimistic Rollups, ZK Rollups

It is already widely known that as part of the upgrade to ETH 2.0, Ethereum transitioned from a proof-of-work (PoW) consensus mechanism to a proof-of-stake (PoS).

What is less discussed is how this upgrade will also bring forth the network's transition from a monolithic layer 1 blockchain to a modular network of blockchains.

The way Ethereum plans to achieve modularization is by launching parallel sidechain networks through a process called ‘sharding’.

Sharding is a process in which a database is split into multiple sections to spread out the data load from the network. By creating new chains called ’shards,’ the Ethereum network will reduce network congestion and increase transactions per second for each shard.

In the beginning, there will be just 64 shard chains, with the Beacon Chain being the first shard chain that will become the new PoS mainchain as the ETH 2.0 upgrade is complete.

The Ethereum mainchain will adopt shard chains as a way to enhance scalability on the Ethereum network by reducing network congestion.

L2s like LoopRing, Optimism, and Arbitrum will continue to operate on top of the Ethereum network and inherit the security of the Ethereum mainchain by having all withdrawal transactions from the L2 validated on the mainchain and stored across multiple shard chains.

Since shard chains operate like independent blockchains, L2s could also be formed on a shard to enhance each shard’s scalability further.

Optimistic Rollups and zk-Rollups

The two main methods of transferring value between Shards or L2s and the Ethereum mainchain are Optimistic rollups and zk-Rollups.

Both offer different approaches for the Ethereum mainchain (consensus layer) to confirm the true state of operations on the execution layers (i.e., account balances and total values in each L2) without validating every single transaction.

Optimistic rollups submit transaction data to the Ethereum network and leverage a dispute resolution system for detecting fraudulent transactions to ensure that all submitted transactions are valid.

The party responsible for submitting batches of transactions to the Ethereum network must post a bond of ETH that can be taken away (slashed) if their submission is discovered to be fraudulent.

Zk-Rollups enable thousands of layer 2 transactions to be bundled into one transaction and then transmitted and validated by the Ethereum network without the Ethereum nodes knowing the details of each transaction.

ZK-Rollups leverage ZK-SNARKs to offer greater scalability to the Ethereum network by only requiring the Ethereum nodes to verify the proof of computation of batches of transactions rather than verifying each transaction on the mainchain.

The Case for Horizen as the Ultimate Modular Blockchain

Modularization is an absolute necessity for blockchains to evolve beyond their initial utility for storing and exchanging data in a decentralized manner.

To deliver multi-purpose applications across a variety of industries while maintaining decentralization, blockchains must be broken up into multiple components that are optimized for transaction execution, consensus/security, and data storage.

The glue that ties these modular components together is the consensus layer, where truth needs to be determined by the network’s most decentralized and censorship-resistant component.

Horizen stands out from other modular architectures because it adopts a PoW consensus mechanism for its mainchain while operating the largest node network in the industry with over 35,000 nodes.

An Efficient Cross-Chain Transfer Mechanism

The value of the execution layer is not just in its ability to process transactions at a higher speed, but also in how efficiently it can transfer information to the mainchain.

If the mainchain has to validate all transactions that occur on the L2 or sidechain, it cannot afford to adopt a consensus mechanism like PoW because transaction speeds are too slow. Therefore, it must opt for a faster yet less secure consensus mechanism like PoS (Solana, Cosmos, Polkadot, Ethereum 2.0) or DAG (Avalanche).

By leveraging ZK-SNARKs, the Horizen mainchain is relieved of much of the burden of validating transactions that occur on the execution layer because it only needs to verify proof of computation of transactions, which takes up significantly less data.

This allows the mainchain to maintain a more decentralized and, therefore, more secure consensus mechanism. It has no need to increase transaction speeds to keep up with the growing number of transactions on the execution layer.

Furthermore, ZK-SNARKs allows traditional companies to leverage the security of a public network while maintaining privacy through their own permissioned blockchain.

The case for Horizen having the ultimate modular blockchain architecture is really a case for security and privacy-preserving technologies being the key aspects of what makes a modular blockchain architecture superior.

Suppose we assume the mainchain is the final arbiter of truth and is supposed to be the most secure and decentralized chain.

In that case, it stands to reason that it should not inhabit the same consensus mechanism as its sidechains or L2s that are optimized for speed or some other quality.

To illustrate this point, imagine you were typing up a very important essay on Google Docs. You feel confident knowing that your hard work is being automatically backed up on Google's Cloud servers every few minutes.

However, would you feel the same way if you found out that Google’s entire cloud server infrastructure was secured by nothing more than a six-letter password and basic two-factor authentication system?

You wouldn’t because you expect that the security standards of your backup storage system should be higher, or at the very least different, than your consumer-facing application.

This is similar to how one should think about the consensus mechanism of a scalability-optimized sidechain versus a final settlement layer mainchain.

In a proof-of-stake dominated modular blockchain architecture, there is an inherent risk of centralization caused by the simple fact that money begets money.

In other words, as a validator who holds a large amount of tokens on one chain, it is easier for me to become a large token holder and dominant validator on another PoS chain because I can simply exchange a portion of my wealth for the tokens of the new chain.

In fact, as a wealthy individual, I would likely have access to these newer tokens before other participants, which means I also get to accumulate them at favorable prices.

This can lead to a situation where a small group of participants make up the majority of validator nodes across multiple interconnected PoS chains, creating centralization and censorship risk for the entire ecosystem.

By anchoring a modular blockchain system to a proof-of-work-based mainchain, you create a counterbalance to this centralization risk because the advantages associated with being a large token holder on a PoS chain do not necessarily translate over to being a dominant miner on a PoW chain.

With PoW, there are other external factors such as the accumulation of mining rigs, which is more a factor of supply chain dynamics than money, and the operation and maintenance of facilities which require a strong understanding of mining economics.

How much space is needed to store my rigs? What is the cost of cooling? How do I acclimate to difficulty adjustments? etc..

It is for this reason that there is very little overlap between the largest ETH validators and the largest Bitcoin miners, which is something that ultimately benefits the crypto space as a whole because it allows for more diversity amongst those whose actions could have a large impact on the stability of the ecosystem.

In order to design the ideal modular blockchain architecture, it is important for both PoS and PoW consensus mechanisms to co-exist because they each act as a check against the other due to the limited transferability of privilege between validators and miners.

This coexistence is also essential for institutions to adopt Web3 platforms and deploy high-value assets on sidechains and L2s, knowing that the data is reinforced by PoW, which is the most secure and battle-tested consensus mechanism available.

When it comes to data storage, critical features like Sharding will not be available on Ethereum 2.0 until 2023.

Meanwhile, on Horizen, it is currently possible to drastically increase data storage capacity (i.e., (transaction throughput) by operating up to 10,000 parallel sidechains simultaneously using Horizen’s recently launched sidechain protocol - Zendoo.

Ultimately, the best modular design offers a highly scalable and flexible infrastructure to allow Dapps to achieve commercial viability while simultaneously offering trustless and censorship resistance validation and storage of high-value digital assets.

Striking a balance between these two opposing qualities will enable the next generation of blockchains to succeed in onboarding millions of users and institutions from the traditional economy.