The UTXO vs Account Model

For digital money to be useful, it needs to be transferable. The transfer of money on a blockchain is initiated by the owner, creating a transaction.

This transaction informs the network about how much money is changing hands and who the new owner is.

Most blockchains use the UTXO model for accounting.

A UTXO, or Unspent Transaction Output, represents the amount of digital currency remaining after a transaction has been executed.

The second method to track user balances, as applied in Ethereum, is the account model.

The Blockchain as a State Machine

Before we get into the different balance models, it makes sense to take a step back and look at the blockchain in more general terms - as a state machine.

A system is described as stateful, only if it is configured to remember preceding events or user interactions. The retained information is defined as the state of the system. Hence, a blockchain qualifies as a stateful system.

Its entire purpose is to record past events and user interactions. With each new block the system undergoes a state transition that happens according to the state transition logic defined in its protocol.

Every blockchain, no matter if it uses the UTXO or account model, follows this scheme:

- The user interactions, mostly transactions, are broadcast to the network, and with each new block, a set of them is permanently recorded.

- The balances of the transacting parties are updated when the system transitions to the new state.

The difference between the UTXO and the account model lies in the way the bookkeeping is handled. With bookkeeping, we mean recording the state and transitioning from one state to another.

Recording the State

The first significant difference between the two balance models is how the state of the system is recorded.

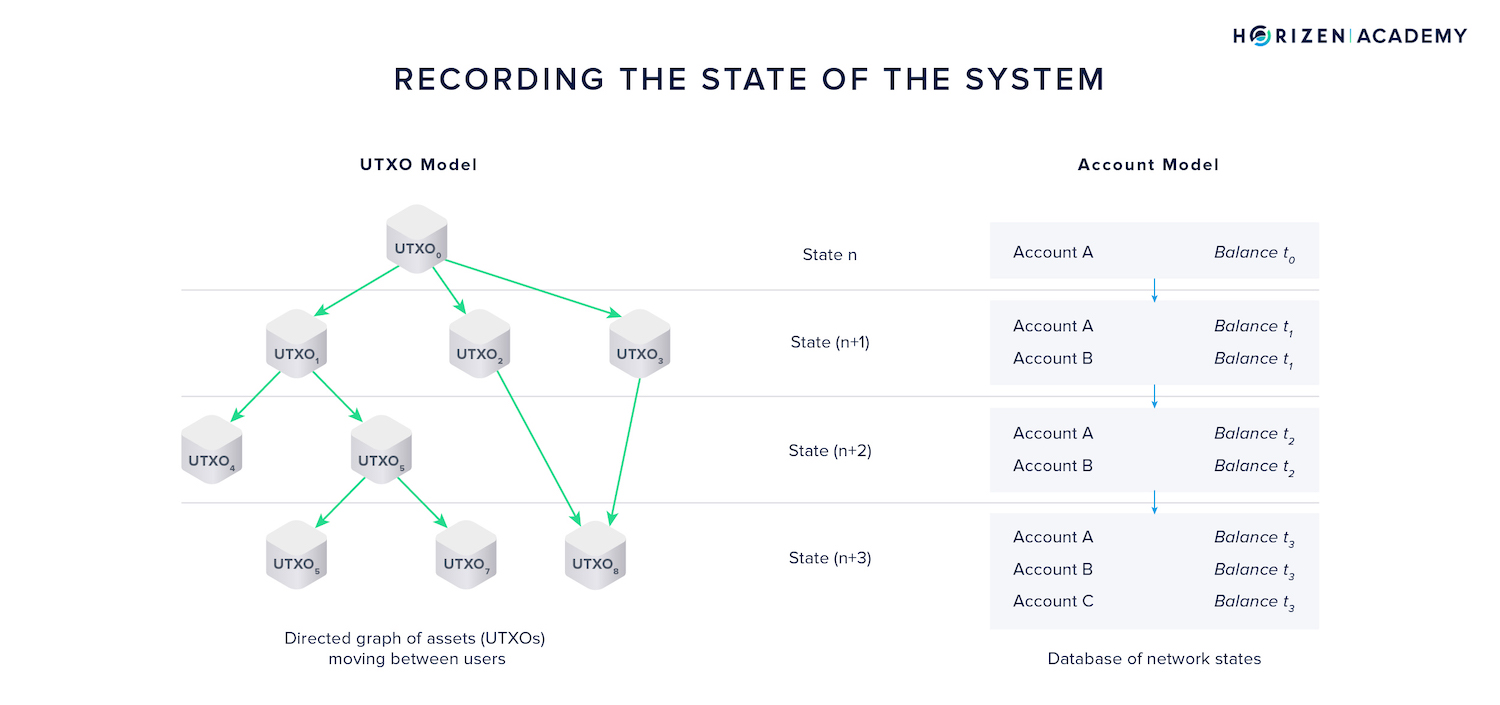

In the UTXO model, the movement of assets is recorded as a directed acyclic graph (DAG) between addresses, whereas the account model maintains a database of network states.

A graph is defined as a set of nodes or vertices connected by edges.

In a directed graph, each edge has a direction, usually indicated through arrows.

Directed acyclic graphs don’t allow circular relationships between node. The graphic above shows a directed acyclic graph of the UTXO model on the left.

Each state represents a block in the blockchain. Each transaction output comprises a node in the DAG, and each transaction is represented by one or more edges originating from a transaction output.

Hence, an unspent transaction output does not have an edge originating from it. In the example above, the transaction outputs 3, 5, 6, and 7 are unspent.

On the right, the graphic shows a representation of the different states in the account model. With each new block, the state of the system is updated according to the transactions contained in the block.

The number of accounts remains constant and independent of the number of transactions conducted, as long as the number of users or smart contracts remains constant.

In the UTXO model, the entire graph of transaction outputs, spent and unspent, represents the global state.

In the account model, only the current set of accounts and their balances represents the global state.

In the example above, this is the set of accounts A, B, and C and their respective balances.

The conceptual difference is that the account model updates user balances globally. The UTXO model only records transaction receipts.

In the UTXO model, account balances are calculated on the client-side by adding up the available unspent transaction outputs (UTXOs).

The UTXO Model

The UTXO Model does not incorporate accounts or wallets at the protocol level. The model is based entirely on individual transactions, grouped in blocks.

We can compare this to people holding certain amounts of cash.

- A user that holds 50 ZEN might be in control of a single UTXO worth 50 ZEN, or a combination of UTXOs that add up to 50 ZEN.

- Comparing it to cash, if a user has $50, he might hold a single $50 bill or a combination of smaller denominations.

Transaction outputs must be spent as a whole because the records in previous blocks cannot be edited, or reduced. When a transaction is spending a UTXO, and the user doesn't want to transfer the entire amount of it, the excess money (the difference between the UTXO size and the amount the user is willing to spend) is sent to a self-controlled address as change.

- Spending 10 ZEN from a UTXO worth 50 ZEN means creating two outputs in the transaction:

- An output of 10 ZEN to the payee

- And a change output of 40 ZEN to the original owner

- Spending $10 with a $50 bill means handing your money over, and receiving $40 in change from the payee afterward.

However, there are two crucial differences:

- In a cash payment, you rely on your counterparty to return the change.

- In the case of the UTXO model, the payee is never in control of the change in the first place.

The other difference is that cash exists in defined, discrete denominations. There are $1, $5, $10 bills, and so on.

Transaction outputs in the UTXO model can have arbitrary values, for example, 11.79327 ZEN.

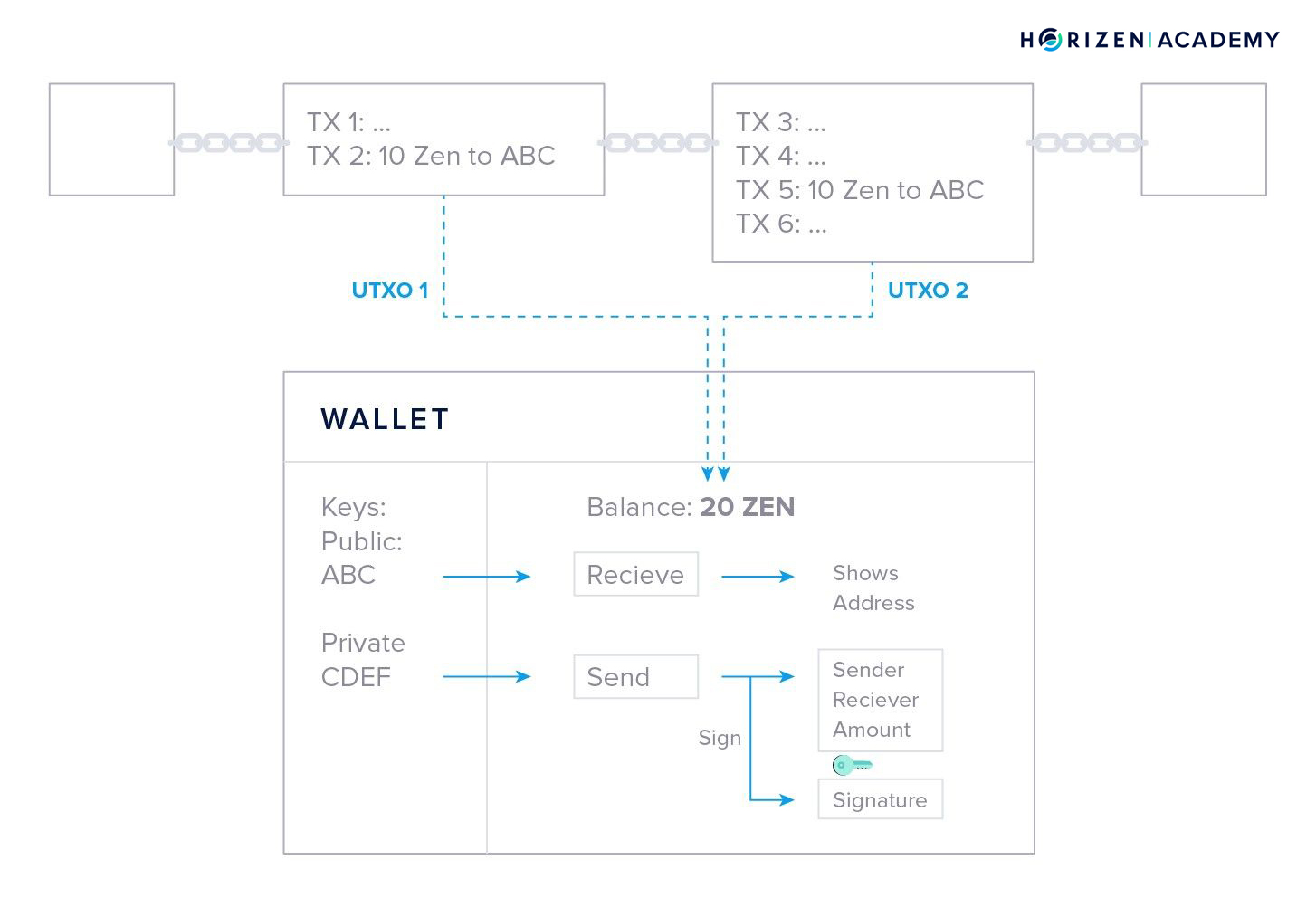

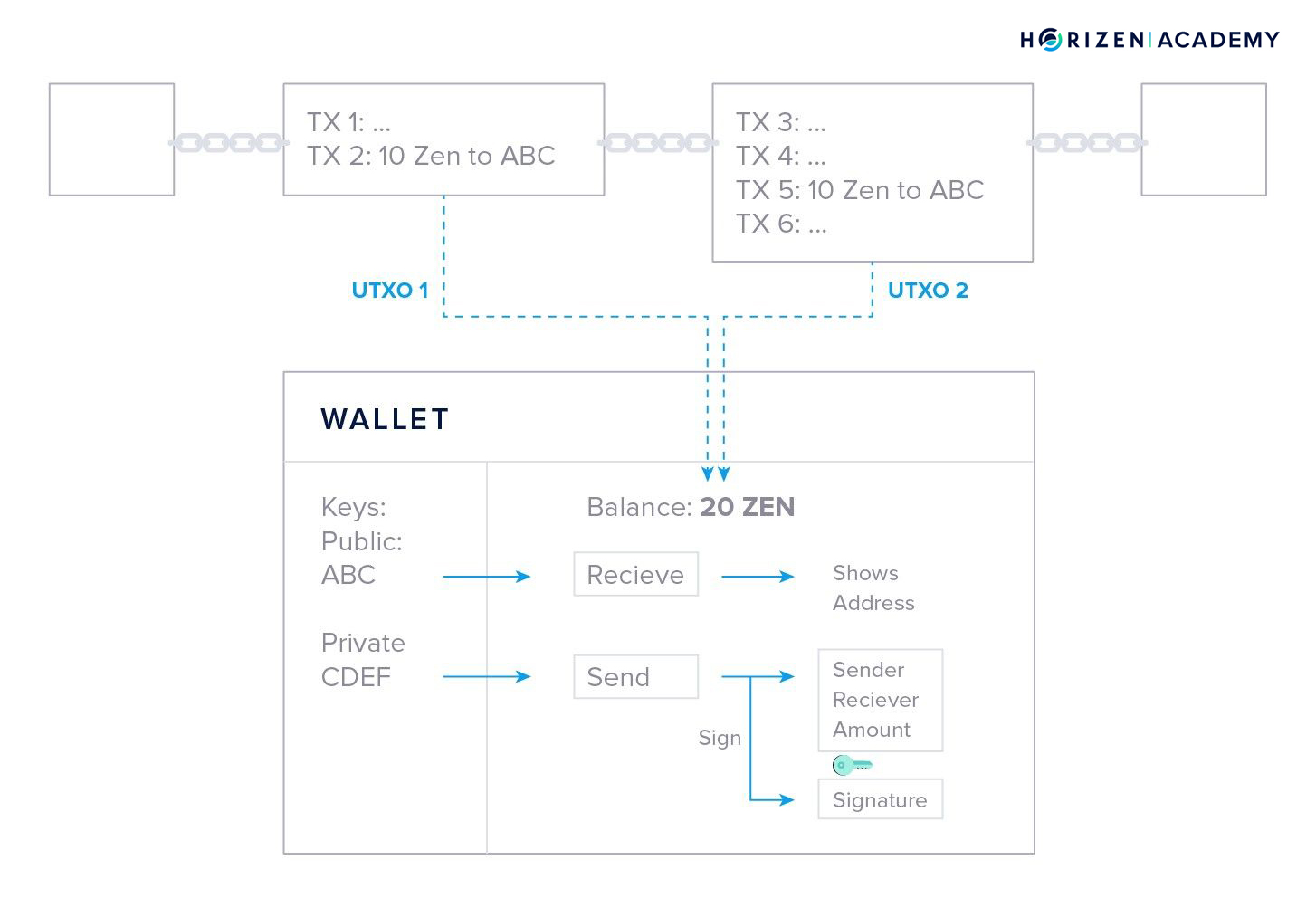

Since there is no concept of accounts or wallets on the protocol level, the "burden" of maintaining a user's balance is shifted to the client-side. Wallets maintain a record of all addresses controlled by a user and monitor the blockchain for all associated transactions.

The sum of all unspent transaction outputs it can control determines the current balance.

State Transitions in the UTXO Model

Each transaction in the UTXO model can transition the system to a new state, but transitioning to a new state with each transaction is infeasible. All network participants must stay in sync on the current state.

Designing a consensus mechanism that keeps all nodes synchronized becomes harder, when state transitions happen more frequently. This becomes intuitive when you consider that the time interval between blocks gives nodes the chance to download the most recent block and process it.

The shorter the period for nodes to update the state, the higher the chance of reaching an inconsistent state where some nodes have a different view of past events than others. As a result, transactions are batched into blocks, and each new block presents a system state transition.

UTXO State Transition Example

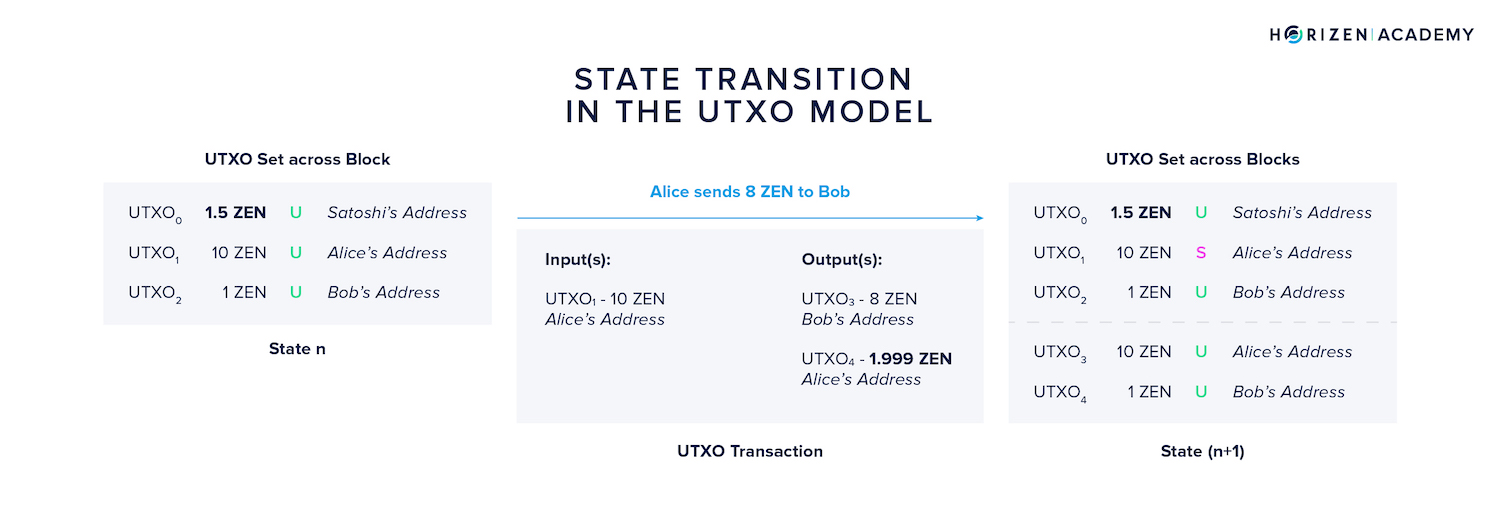

In the example below, we look at a UTXO state transition with only a single hypothetical transaction for simplicity.

Assume Alice wants to transfer 8 ZEN to Bob, and she controls a single UTXO worth ten ZEN. The transaction she creates consumes her previously unspent transaction output \(UTXO_1\) as an input.

To spend a UTXO, it needs to be "unlocked."

The Pubkey Script included in each transaction output defines the spending conditions. The data necessary to satisfy this script is provided with the spending transaction and includes the digital signature of the owner - in this case Alice.

Next, she defines what should happen to her money. She does this by creating transaction outputs.

Alice wants to transfer 8 ZEN to Bob, so she creates two outputs:

- One paying Bob

- And another returning the excess money to a self-controlled address.

For both outputs, the spending conditions are also defined in the transaction created by Alice.

Note how the sum of outputs doesn’t equal the entirety of the consumed input. The difference between outputs and inputs is defined as the transaction fee on the protocol level. In this case, the TX fee is 0.001 ZEN.

The transaction fee’s size is estimated by the wallet based on the amount of data recorded on-chain.

Miners can only place a limited amount of data within a block, and by using the metric ‘money per amount of data,’ miners can determine which transactions to include in the block. They will typically pick the transactions with the highest fees per byte.

The UTXO Model in Action

When you think about how your bank does the accounting for your bank account it is pretty intuitive.

- You hold a certain amount of money in your account which has an account number.

- If you receive money the amount is added to your balance.

- If you spend money, then the amount you spend gets subtracted from your balance.

The blockchain does not create an “account” for you to maintain a balance. There is no final balance stored on the ledger. The blockchain only stores individual transactions and to check your balance, there is an additional step involved.

Your wallet does this automatically whenever you open it. What happens in the background is that your wallet scans the ledger for all transactions to your address(es) and adds them up.

Each transaction on the blockchain has one or more inputs and one or more outputs.

Let’s have a look at an actual example throughout a series of four transactions:

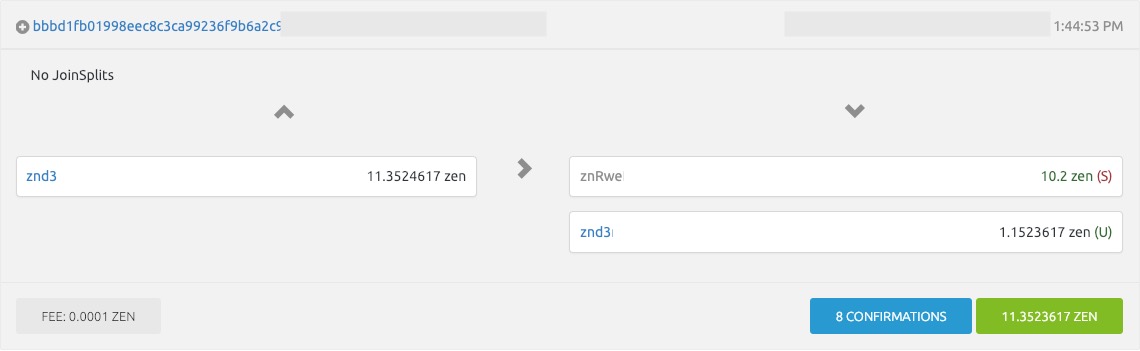

Usually, a block explorer will show you the most recent transactions first.

For this example, we will go through the transactions as they happened - in chronological order. This simple example only involves two different addresses.

We shortened the addresses for better readability.

The address we are concerned with here is the gray one: znRwe…

Let’s say this is Bob and the other one in blue, is Alice.

Bob Receives His First Transaction

In the first transaction, or TX, above, Bob’s address znRwe... is funded when he receives 10.2 ZEN.

The TX has one input and two outputs. The first output of 10.2 ZEN is what Alice actually wanted to transfer to Bob, the second output is called the change output.

The input that Alice was using, was an output of a transaction she received before. When she still had her money untouched, it was an Unspent Transaction Output (UTXO).

A spent transaction output is indicated by the (S), a UTXO is indicated with a (U) following the amount.

Alice didn’t have a UTXO that was exactly 10.2 ZEN so she used one that was larger and sent the remaining ZEN back to herself, just as you would receive change in a store if you were to pay $45 with a $50 bill.

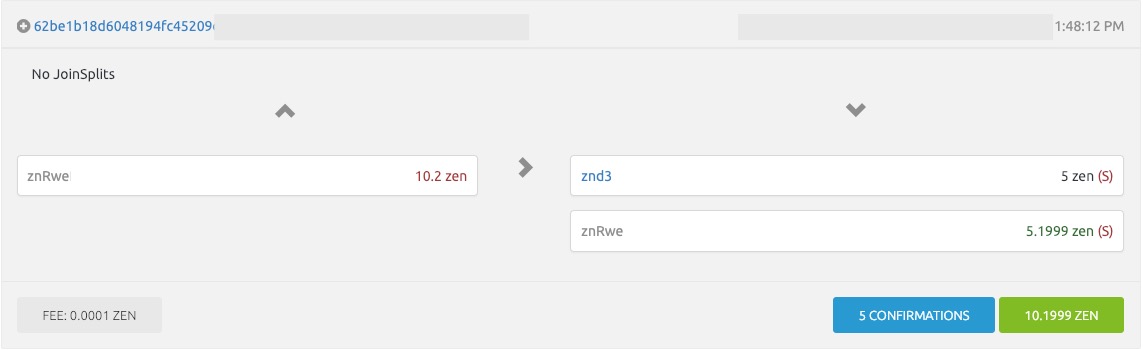

Bob Sends His First Transaction

In the second transaction, Bob spends his UTXO of 10.2 ZEN and creates a transaction with two new UTXOs: one of 5 ZEN to a different address and one of 5.1999 ZEN back to his own address - the change output.

The difference between inputs and outputs - 0.0001 ZEN - is consumed as the transaction fee. He now owns 5.1999 ZEN on his znRwe… address.

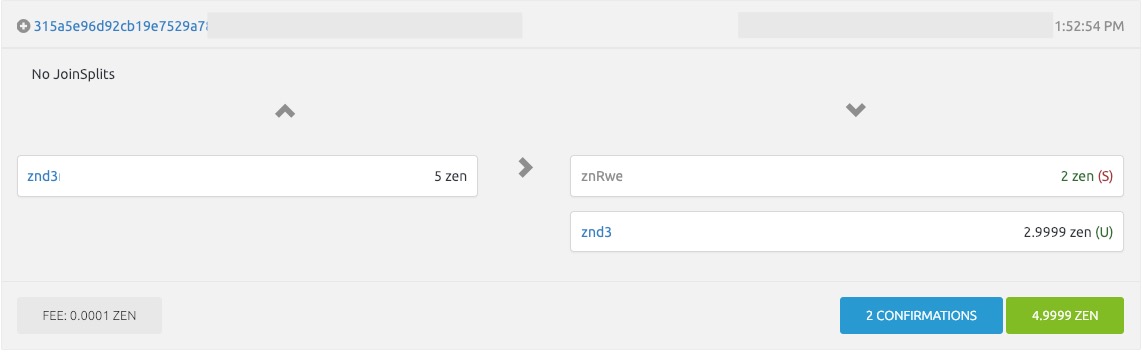

Another UTXO

In a third transaction, Bob receives another 2 ZEN, increasing his balance to 7.1999 ZEN.

He now has two UTXO's at his disposal for further transactions: one of 5.1999 ZEN and another one of 2 ZEN.

If he were to open his wallet at that point, it would show him a balance of 7.1999 ZEN by looking at all transactions on the blockchain, filtering out the ones that involve his address and then adding up all unspent outputs.

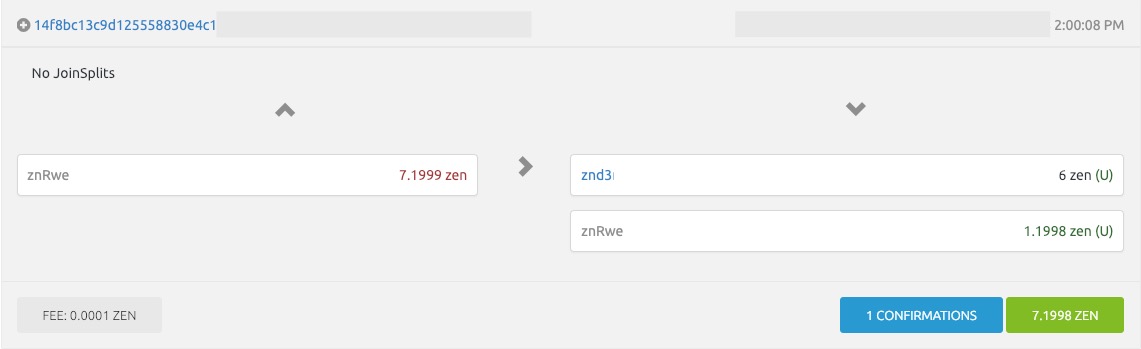

Spending Two UTXOs at Once

In the last transaction of this example, Bob wants to spend 6 ZEN. Neither of the two UTXO's he has at that point is sufficient for that purpose.

Although the block explorer shows only one input for the last transaction there were clearly two inputs used: the 5.1999 ZEN and 2 ZEN one from the two examples above.

Combined both UTXO's are worth 7.1999.

Bob created two outputs with it: the 6 ZEN output he actually wanted to spend and an additional output for the change of 1.1998, 1.1999 minus the transaction fee of 0.0001.

You can see that by now both TX outputs are spent, indicated by the (S) next to them in the second and third screenshot.

The Account Model

The account-based transaction model represents assets as balances within accounts, similar to bank accounts. Ethereum uses this transaction model.

There are two different types of accounts:

- Private key-controlled user accounts

- Contract code-controlled accounts

When you create an Ether wallet and receive your first transaction, a private key controlled account is added to the global state and stored across all nodes on the network.

Deploying a smart contract leads to the creation of a code controlled account. Smart contracts can hold funds themselves, which they can redistribute according to the conditions defined in the contract logic.

Every account in Ethereum has a balance, storage, and code-space for calling other accounts or addresses.

A transaction in the account-based model triggers nodes to decrement the balance of the sender's account and increment the balance of the receiver's account. To prevent replay attacks, each transaction in the account model has a nonce attached.

A replay attack is when a payee broadcasts a fraudulent transaction in which they get paid a second time. If the fraudulent transaction were to be successful, the transaction would be executed a second time - it is replayed - and the sender would be charged twice the amount they wanted to transfer.

To combat this behavior, each account in Ethereum has a public viewable nonce that is incremented by one with each outgoing transaction. This prevents the same transaction being submitted to the network more than once.

Transaction fees also work differently in the account model: they are calculated based on the number of computations required to complete the state transition. Ethereum set out to be a world computer.

Hence they decided that fees should be based on the number of computational resources consumed rather than storage capacity taken.

The account model keeps track of all balances as a global state. This state can be understood as a database of allaccounts, private keys, and contract-code controlled along with their current balances of the different assets on the network.

The global state in the UTXO model is the set of all transaction outputs. The global state is always the entire graph of UTXOs.

The state in the account model is the list of accounts and their balances. So in the second graphic, the global state (n+3) is this list of 3 accounts (A, B, and C) and their balances.

The main difference comes down to the global state in the UTXO model being only extended with new UTXOs, whereas in the account model, the global state is updated and balances change.

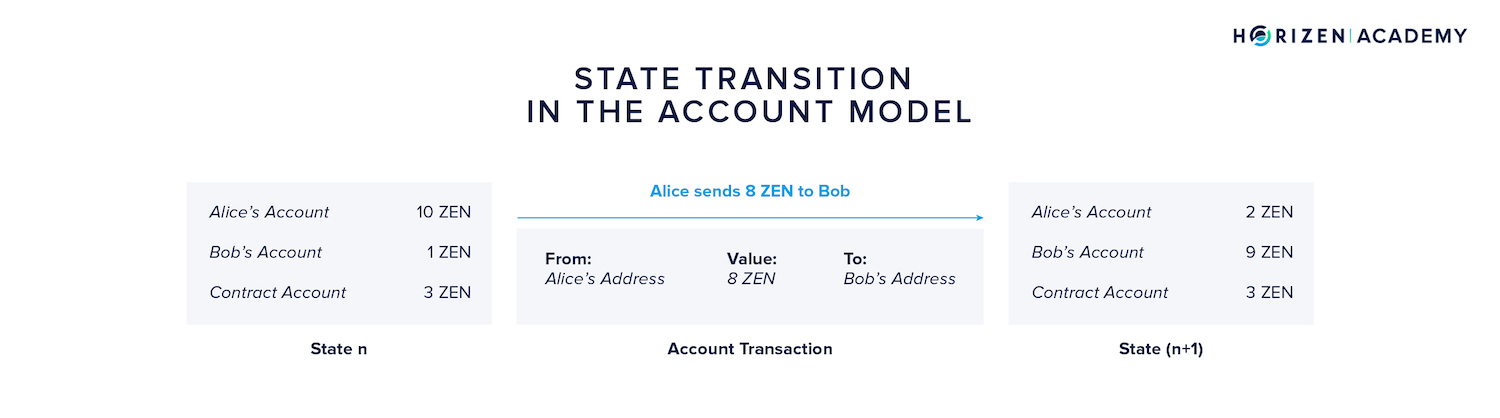

State Transitions in the Account Model

In a straightforward model, a transaction presents an event that triggers a state transition of the blockchain subject to the state transition logic. Just like in the UTXO model, it is infeasible to transition the system to a new state with every transaction without risking an inconsistent state.

Transactions are also batched into blocks in the account model, and with each new block, the system transitions to a new state. Just like we did before, we consider a simple example where a single transaction transitions the system to a new state below.

The setting is the same as before: Alice wants to transfer 8 ZEN to Bob.

Her wallet will create a transaction that defines the spending account, the receiving account, and the amount to transfer. This transaction is then signed with Alice's private key. In this case, she is spending from her address, the receiver is Bob, and the amount to transfer is 8 ZEN.

When the system transitions to a new state (n+1) with the next block, Alice's account balance will globally be reduced to 2 ZEN, whereas Bob's balance will be increased to 9 ZEN.

The PubKey and Signature Script do not exist in account-based blockchains.The verification of signatures in account-based blockchain, Ethereum for example, is based on three parameters, r, s, and V provided by the sender.

These three values comprise the signature. Solidity, the programming language used in Ethereum, provides a method, ecrecover, that returns an address given these parameters. If the returned address matches the sender's address, the signature, and in return, the transaction is valid.

Where in the UTXO model part of the verification process is checking if a transaction output in unspent, nodes in the account model check if the sender's balance is larger than or equal to the transferred amount. This is true for the native asset of the chain, for example Ether, as well as all other tokens on the network.

A transaction in the account-based model is an instruction for how to transition two or more accounts to the next state. The actual transition is executed by the nodes. Because the final state is not specified in the transaction, the resulting transaction size is a lot smaller than in the UTXO model.

The state of accounts in Ethereum is not stored on the blockchain but computed and stored locally by the nodes. The blockchain only stores the instructions, read as transactions), for how the system should transition from one state to another.

Comparing the UTXO and Account Model

In short, The UTXO model is a verification model.

This means users submit transactions that specify the results of the state transition, defined as new transaction outputs spendable by the receiver(s). Nodes then verify if the consumed inputs are unspent and if the signature(s) satisfy the spending conditions.

The account model, on the other hand, is a computational model.

In this model, users submit transactions instructing nodes on what state transitions should look like. The network then computes the new state based on the instructions.

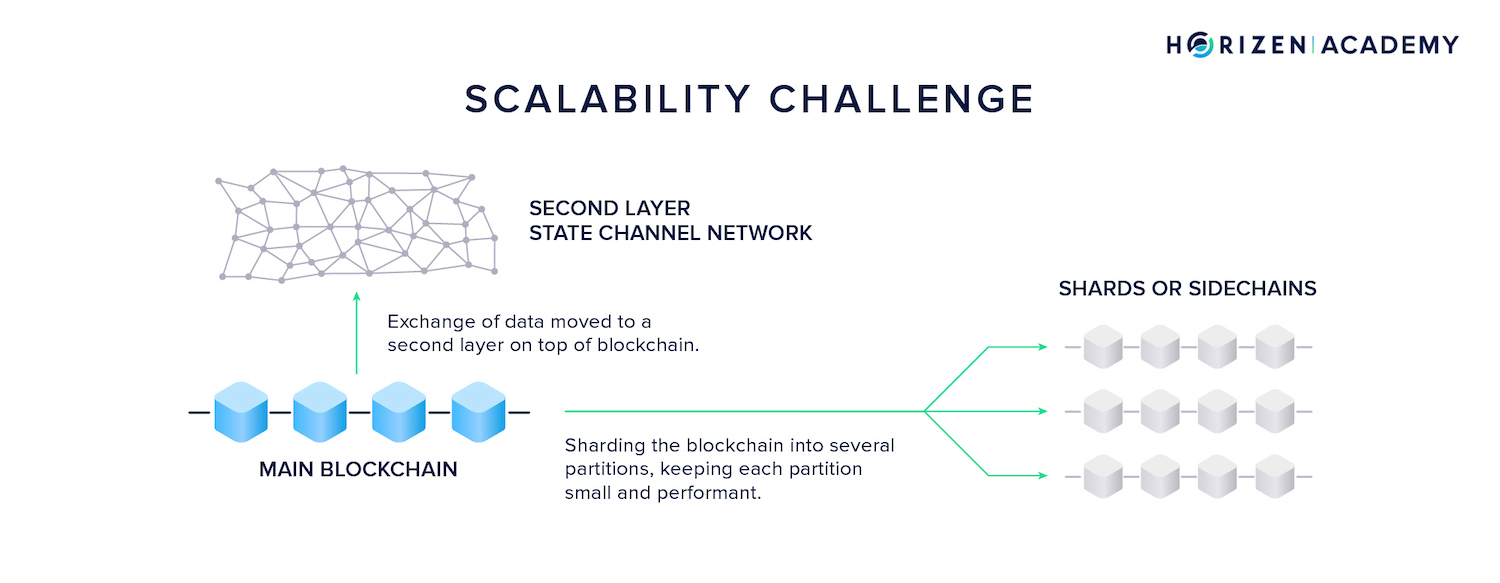

This method comes with specific implications regarding second layer scalability solutions like state channels and sharding.

Scalability - UTXO vs Account

There are several approaches we can use to compare the scalability of the UTXO and the account model.

- One way is to focus on the overall storage requirements of each system.

- Another way is to consider which model is better suited for the deployment of second-layer technologies on top of the main blockchain.

One second layer technology, state and payment channels, moves the exchange of data from the blockchain to a dedicated trustless network of bidirectional communication channels.

The other approach that could arguably be referred to as a second layer technology is sharding. Sharding is a term originating from the traditional database world.

Sharding describes partitioning a database into several shards in order to keep each individual partition more performant, in turn improving the entire system. Horizen's sidechain can be considered a sharding mechanism.

We'll now compare both accounting methods and will assume that both systems have similar user and transaction counts.

Size of the Blockchain

The account model has more efficient memory usage.

Storing a single account balance saves memory compared to storing several UTXOs that comprise a user's total balance. Transactions in the account model are also smaller in size because they only specify the sender, receiver, the transfer amount, and a single digital signature.

Additionally, just by doing away with change outputs, a lot of data can be saved in the account model.

On a conceptual level, this is intuitive. Since a UTXO transaction specifies the state after the transition, the newly generated transaction outputs), it needs to include more data than an account transaction. It may also consume several UTXOs as inputs, whereas the account transaction only specifies which account balance to deduct an amount from.

To give you an idea, Ethereum's account model takes about 100 bytes, whereas a UTXO transaction in Horizen takes about 200-300 bytes.

This also means that it's faster to get new nodes online in a system running the account model because less data is needed to get them in sync. The number of accounts will generally be much smaller than the total UTXO set in a comparably sized system.

State and Payment Channel Constructions

Currently, the most advanced payment channel construction is the Lightning Network on Bitcoin. It uses a proof submission and verification mechanism as assets move into and out of the second layer.

As mentioned above, the UTXO model is essentially a verification model, whereas the account model is a computational model. Hence, a UTXO construction is more suitable for these types of scalability approaches.

Sharding

Partitioning a blockchain into shards or sidechains is also easier while using the UTXO model. Aggregating spendable transaction outputs and defining the outputs happens on the client-side, reducing the stress on the overall system.

In the account model, every node has to localize the sender's and receiver's account across different shards and edit both. Of course, there is more to sharding than these rather straightforward modifications, and using one balance model over the other comes with second and third-order effects.

Generally, the UTXO model allows data structure partitioning more simply.

Privacy

When it comes to privacy, there are merits to both the UTXO and the account model.

The UTXO model makes it harder to link transactions, whereas the account model provides better fungibility.

When change addresses are consequently used in the UTXO model, it makes tracking the ownership of coins harder compared to the account model. A newly generated address doesn't have a known owner and requires advanced chain analysis to be linked to a single user.

The account model implicitly encourages address reuse and hence makes creating a transaction history for a single user easier.

With regard to fungibility, the account model offers better privacy. There is complete transparency of UTXO movements, read as assets, in the UTXO model when no privacy-preserving techniques are applied. However, the account model comes with a built-in "coin mixer" of sorts.

When an account is funded with several transactions, the result is a single balance. When a payment from this account is made, an observer cannot determine which of the incoming coins is being spent.

Consider the example of the account model above where Alice sends 8 ZEN to Bob, and his balance is updated to 9 ZEN. When Bob subsequently spends 1 ZEN, nobody can determine if the single ZEN stems from Alice or a different source.

This is a very simplified view. Even when assets cannot reliably be assigned to a funding transaction, analytic tools can determine if coins are tainted, but the general idea remains.

Smart Contract Capabilities

The account model offers clear advantages when it comes to enabling smart contracts.

First, the account model logic is more intuitive. Adding and subtracting balances makes it easier for developers to create transactions that require state information or involve multiple parties. A signed transaction is valid as long as the sending account has a sufficient balance to pay for the execution.

Checking a balance is computationally less expensive than verifying if a transaction output is spent or unspent.

This is especially true for code controlled accounts that interact with other smart contracts. Internal transactions between contracts can be carried out in a virtual machine by adjusting the balances of the contracts.

The UTXO model creates computational overhead because all spending transactions must be explicitly recorded. Smart contracts in a UTXO model would need to include logic for choosing which outputs to use when sending assets, and logic to handle change outputs.

Because the UTXO model is inherently stateless, it forces transactions to include state information, complicating the overall design.

Other Differences

One benefit of the UTXO model is that it allows for the simpler parallelization of transactions in smart contracts. Multiple UTXOs used in different transactions can be processed at the same time since they all refer to independent inputs.

In the account model, the result of a transaction depends on the input state. Executing transactions in parallel must be handled carefully. Generally, transactions affecting the same account should be executed sequentially.

A key takeaway is that the UTXO model is better when dealing with simple transactions. The account model is beneficial when dealing with more complex logic.

Hence a popular trend with current smart contract platforms is using a hybrid model where the UTXO model is used for balances, and the account model is used for smart contracts.

Hybrid Systems

QTUM is one example of a blockchain that utilizes a hybrid system of UTXOs and accounts.

"Early on when Qtum was first being designed, the thought process was to build a business-ready blockchain that was versatile yet secure. To accomplish these motivations, Qtum chose the underlying UTXO (Unspent Transaction Output) model that Bitcoin is built on over the Accounts model that Ethereum style blockchains are built on." - Dev Bharel

The UTXO model was used as the basis for the overall architecture because it was considered significantly securer at the time of conception. On top of this UTXO layer, QTUM enables "creating and executing smart contracts using the account model offered by Ethereum" through a construction they call the Account Abstraction Layer (AAL)

The AAL combines UTXOs for a given contract in a new transaction as soon as there are two or more of them available to the contract code. By using the UTXO model as a base layer, QTUM is also able to implement BlackCoin's Proof of Stake Protocol, which requires parallel proofs and UTXO activity.