Zendoo - Cross-Chain Platform

The Zendoo Protocol

Horizen’s current sidechain implementation, the Zendoo protocol was released early in 2020. It introduces:

“A standardized mechanism to register and interact with separate sidechain systems. By interaction, we mean the Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol, which enables sending a native asset to a sidechain and receiving it back in a secure and verifiable way without the mainchain knowing anything about the internal sidechain construction or operations.”

In more general terms, the Zendoo protocol allows a Bitcoin-based blockchain protocol to operate with any domain-specific blockchain or blockchain-like system. The blockchain protocol is upgraded only once to introduce the mechanism for deploying sidechains and to enable cross-chain transfers.

Zendoo allows backward transfers to be verified by the mainchain without relying on external validators or certifiers. The mainchain does not monitor sidechains (asymmetric peg) and doesn’t know anything about their internal structure. Zendoo accomplishes this by generating recursive proofs for each sidechain state transition.

Main Components in Zendoo

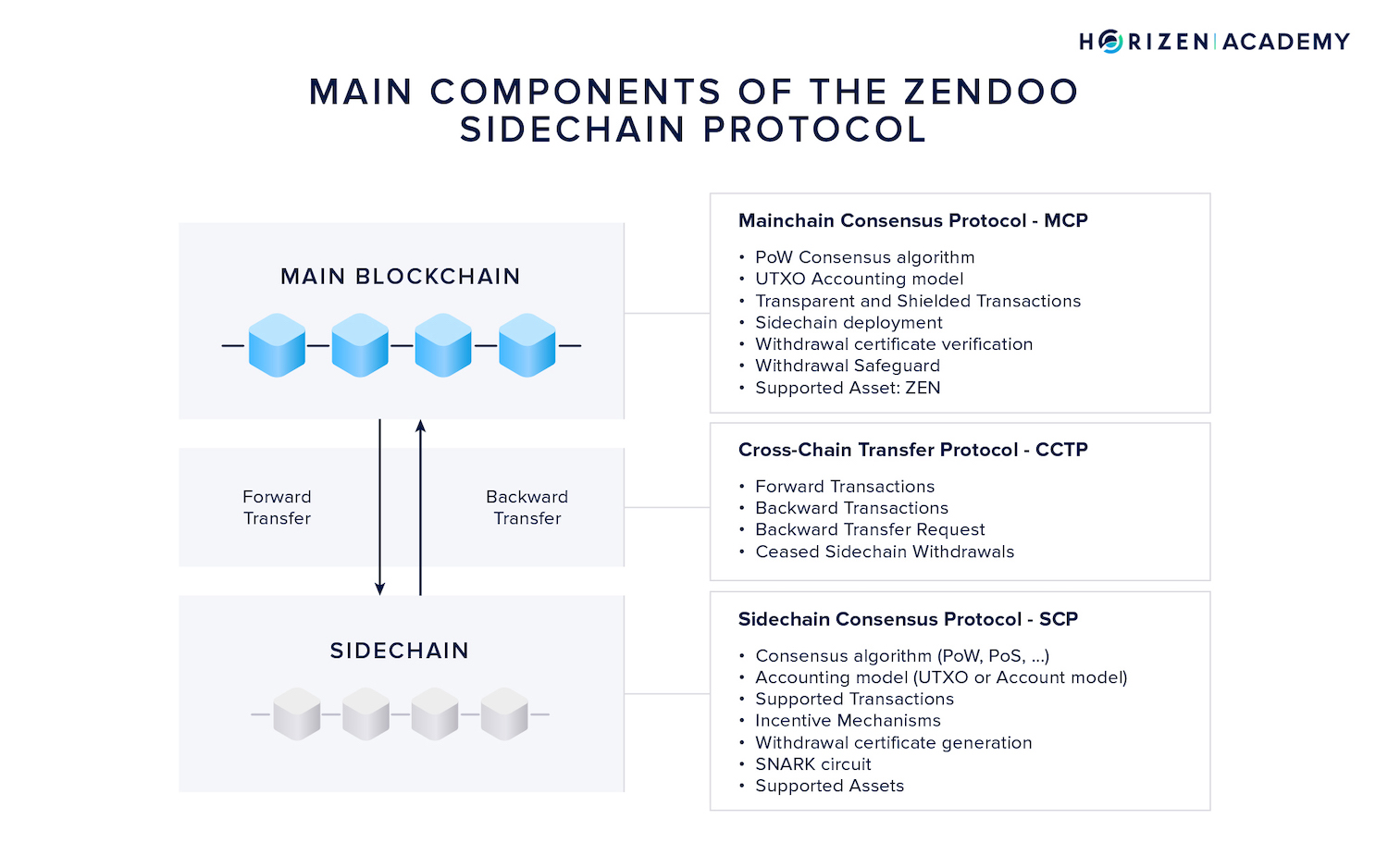

Most sidechain constructions consist of three elements:

- The Mainchain Consensus Protocol - MCP

- The Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol - CCTP

- The Sidechain Consensus Protocol - SCP

Depending on the sidechain structure, these components can be either highly dependent on one another or highly decoupled. The Zendoo protocol allows various degrees of freedom concerning the SCP. The Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol serves as a bridge between MCP and all sidechains.

The Mainchain Consensus Protocol - MCP

Horizen’s mainchain consensus protocol comprises the Proof of Work and Nakamoto consensus algorithm, the UTXO accounting model, and the transaction logic. The Zendoo specific parts of the MCP are the deployment of new sidechains via special bootstrapping transactions, a new transaction type to transfer assets to a sidechain as well as the verification of incoming backward transfers from sidechains.

The Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol - CCTP

The Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol is the bridge between main and sidechain, and is unified and fixed by the mainchain consensus protocol. Its two main components are forward and backward transfers. In forward transfers, ZEN is sent from the mainchain to a sidechain. In backward transfers, ZEN is returned to the mainchain.

Because sidechains monitor the mainchain, they can verify forward transfers themselves. Since the mainchain doesn’t monitor sidechains, Zendoo introduces a mechanism capable of verifying backward transfers without relying on certifiers.

A vital component of the Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol is the Withdrawal Certificate.

This certificate groups all of the backward transfers from a sidechain within a given time period - the Withdrawal Epoch - and broadcasts them to the mainchain.

Every sidechain needs a mechanism to generate valid withdrawal certificates. Each sidechain also needs to define a proof system so the mainchain can verify incoming backward transfers. We’ll get to proof systems shortly.

The Sidechain Consensus Protocol - SCP

The sidechain consensus protocol includes all parameters of the sidechain. Typically, the consensus algorithm would describe the mechanism to agree on a single version of history.

A sidechain in Zendoo can run a different consensus mechanism, accounting model or data structure than the mainchain. The sidechain doesn’t even have to be a blockchain at all, as long as it adheres to the cross-chain transfer protocol, it will be able to communicate with the main blockchain.

A Horizen-compatible sidechain allows for great freedom.

As a first step, Horizen provides a reference implementation for a sidechain consensus protocol named Latus, based on a delegated Proof of Stake consensus mechanism inspired by Ouroboros Praos. A detailed description of the Latus construction is out of scope for this article. We refer the interested reader to our Zendoo paper to learn more.

Modifications of the Mainchain Protocol

Some modifications to the mainchain protocol are necessary to allow the deployment and use of sidechains on a Bitcoin-based blockchain.

- First, and most importantly, a select type of bootstrapping transaction is introduced to deploy sidechains.

- Second, a mechanism to process and verify incoming Withdrawal Certificates is needed.

- Third, a new data field, the Sidechain Transaction Commitment is added to the mainchain block header, where a Merkle root of all sidechain related transactions is recorded.

- Lastly, a withdrawal safeguard is introduced as a mechanism to prevent unforeseen inflation of the coin supply.

In the following sections we will go through the mainchain modifications that allow deploying and using sidechains.

Understanding how the mainchain verifies incoming sidechain transactions without directly tracking them is crucial for understanding all other mainchain protocol changes; hence we will look at this mechanism first.

Verification of Backward Transfers

Most sidechain protocols rely on certifiers acting as a bridge between chains. These entities monitor one or more sidechains, collect and verify backward transactions, and broadcast them on the mainchain. Certifiers can either be a trusted group of centralized actors, or a decentralized group of network participants incentivized to follow the protocol. While we assume an honest majority among verifiers, there is still the possibility of malicious activity.

Ideally, backward transfers are objectively verifiable without the need to rely on intermediaries. This need to remove intermediaries is Horizen’s motivation for building a backward transfer mechanism that relies on a proof system rather than software instances run by human entities.

Proof Systems

On the highest level, a proof system allows a prover to prove to a validator that a given statement is true. Instead of the validator redoing the entire computation to verify the result, the prover can generate a proof for its correctness.

A proof comprises a set of values that the verifier uses to compute a binary output - true or false. When the verification function returns true the computation was performed correctly, if it returns false, it wasn’t.

Verifying state transitions in a system is one great use case for a proof system. A blockchain is a state machine in the sense that every block records new transactions onto the ledger, changing the state of the system. Nodes verify each block before they add it to their version of the ledger.

They check if transactions have valid digital signatures attached, if only previously unspent transaction outputs] are spent, and if the Proof of Work attached to the block meets the current difficulty.

With a proof system, a miner could generate a proof that the state transition (new block) was performed according to the protocol. All other nodes would simply have to verify if the proof is correct and could save themselves from verifying each part of the block individually.

Zero-Knowledge proofs such as zk-SNARKs are best known for their application in privacy-preserving cryptocurrencies. Horizen, Zcash and other protocols utilize zkSNARKs to enable the private transfer of money. When proofs are used to transfer money privately, a user creates a transaction according to the blockchain’s protocol.

Instead of broadcasting this transaction in plaintext to the network, the user generates a proof that the transaction is valid and broadcasts this proof. The proof entails all necessary information about the transaction: the previously unspent inputs and the digital signature(s) satisfying the spending conditions of the inputs.

Once broadcast, nodes will verify the proof instead of the plaintext transaction. For this to work, an essential property of the proof system comes down to soundness and completeness.

- Soundness means a proof can practically not be faked.

- Completeness means that a valid proof always evaluates to true when verified.

While completeness can be mathematically guaranteed, soundness is practically guaranteed, as no entity has infinite, in the literal sense, computational resources.

In Zendoo, sidechains generate proofs of their state transitions. When a withdrawal certificate is submitted to the mainchain, a proof of correct state transitions is attached. Miners on the mainchain verify this proof before including the withdrawal certificate in a mainchain block. This is how an algorithm replaces certifiers.

But how exactly are proofs for state transitions generated? Recursively!

Recursion

To understand the generation of state transition proofs, we need to understand the concept of recursion. Recursion is not only useful for understanding the sidechain design, but also an important concept in general computer science.

Recursion in terms of computer science, is a procedure of solving a problem where the solution depends on solutions to smaller instances of the same problem.

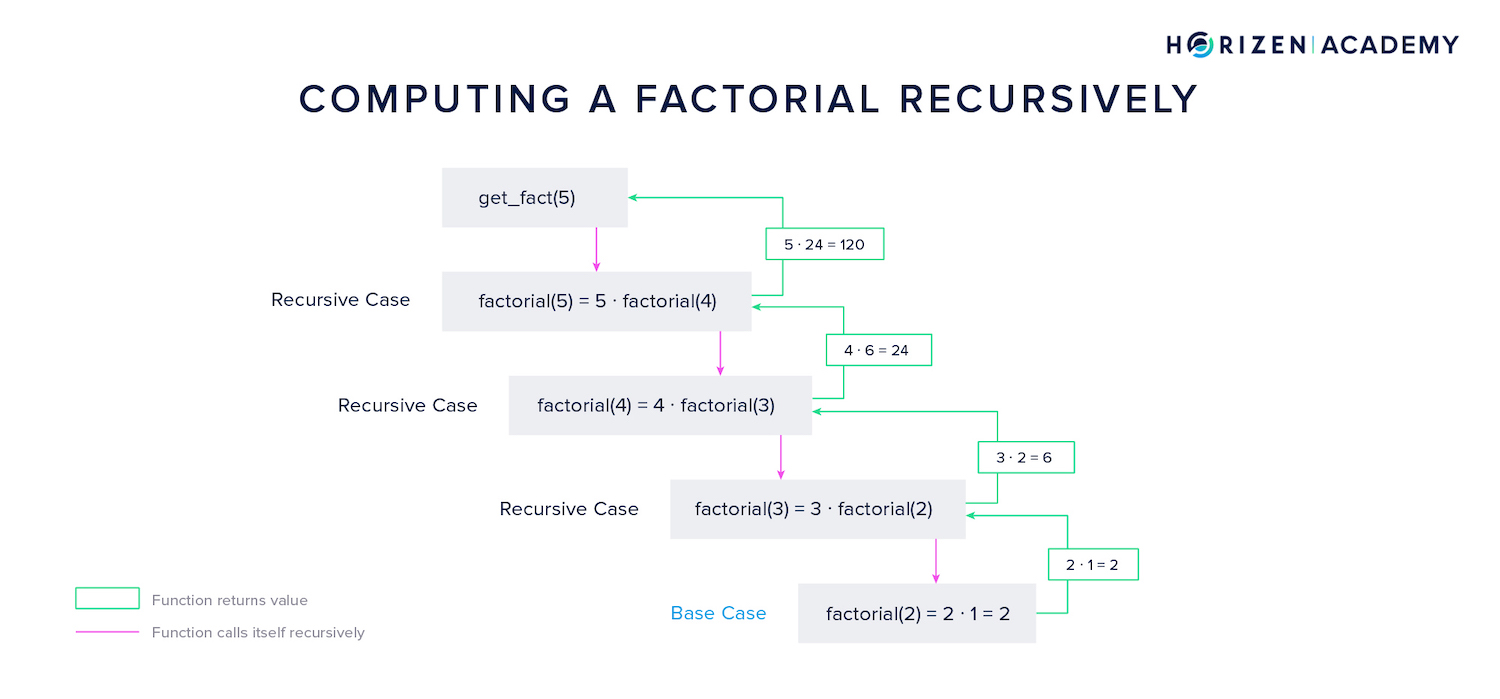

Solving a problem recursively means that the function solving the problem can call itself. This is best illustrated in an example. The most common and intuitive example is calculating the factorial of a given number.

A general expression for the factorial of a number is:

$$ n! = n \cdot (n-1) \cdot (n-2) \cdot ... \cdot 1 $$

Hence, the factorial of 5 is

$$ 5! = 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1 = 120 $$

Writing a function that calculates the factorial of a given number is elegantly achieved using recursion.

The idea is that the factorial of the number 5 is equal to five times the factorial of the number four:

\(5! = 5 \cdot 4!\)

The solution to the problem 5! then depends on a smaller instance of the same problem: 4!.

In the example above, the recursive function starts with the first recursive case \(5! = 5 \cdot 4!\), then starts another instance of the function that computes 4! - and so on. This continues until the base case is reached.

The base case is the factorial of the number 2, which equals 2.

Instances of the function are closed subsequently after returning their result to the function's next highest instance. In the example above, the base case returns 2 to the next highest instance, which will use the result to compute 3!, and so on. In the last step, 120 is returned, and the highest instance of the function is closed.

In C, the function calculating the factorial can be elegantly written. You can see below that the function factorial is used within the function itself (factorial(n-1)). Even without a basic understanding of software development, you might appreciate the simplicity. We can compute the factorial for any given number in just four lines of code.

long factorial(int n)

{

if (n == 0) //Base Case

return 1;

else //Recursive Case(s)

return (n*factorial(n-1));

}

Note: In the graphic before we called \(2 \cdot 1\) the base case for simplicity's sake.

We want to achieve a proof of state transitions in the context of our sidechains. If the state transition is proven, the resulting state and hence all backward transfers are automatically proven. But how does recursion apply to this?

State Transition Proofs

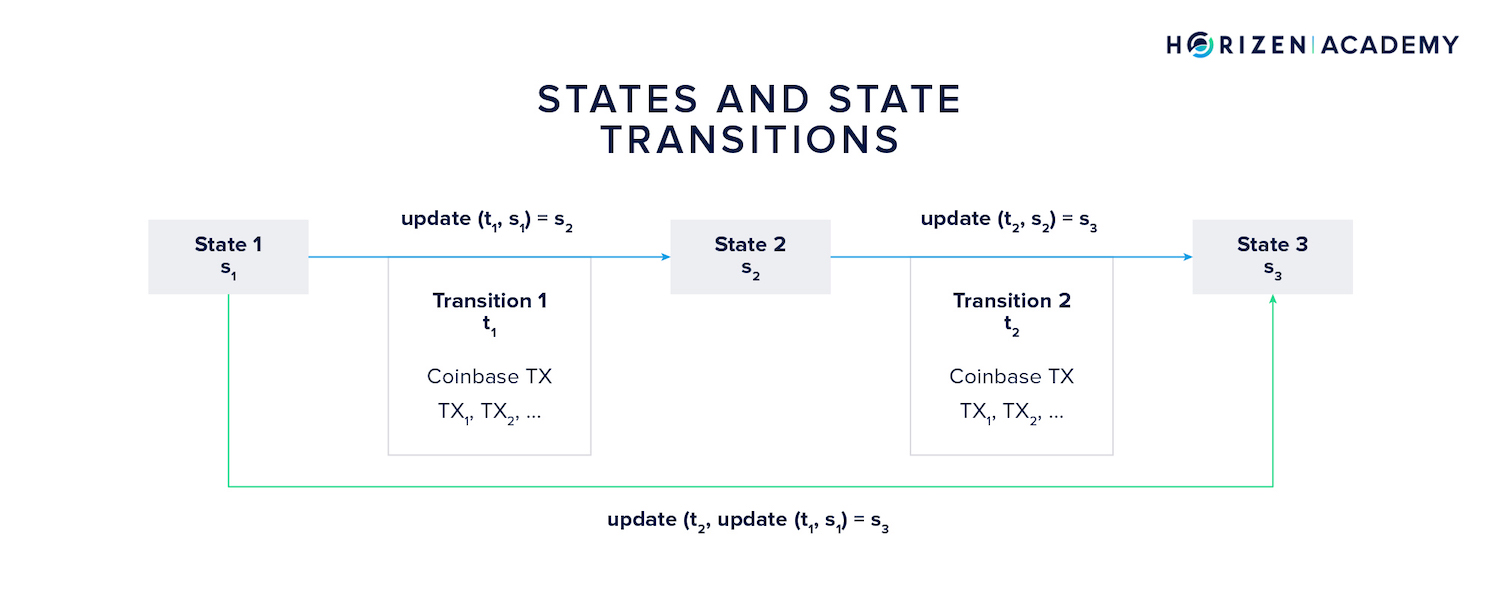

The blockchain's state transition logic is a function that takes the current state \(s*i\) and the most recent set of transactions \(t_i\) as an input, and returns the next state \(s*{i+1}\) as an output. The factorial of five is expressed as the number five times the result of the function for computing the factorial of four. The current state can also be computed based on the current transition and the result of the function for computing the last state. Let us look at a tangible example.

Let's assume a sidechain starts in state 1 \(s_1\) with its genesis block.

The first transition \(t_1\) consists of all transactions included in the first "real" block applied to the first state. The transition function, let's call it update, takes these two parameters, the initial state (Genesis Block) and the first transition (read: transactions), and computes the next state \(s_2\), given the inputs constitute valid arguments to the update function.

$$ s_2 = update(t_1, s_1) $$

The same logic applies for the second state transition. Based on state \(s_2\) and the second transition \(t_2\) the update function computes the third state \(s_3\).

$$ s_3 = update(t_2, s_2) $$

Now, the current state of the sidechain can always be computed from the initial state \(s_1\) and all transitions \(t_i\) the system underwent. It allows one to subsequently compute every state the system went through. In our example, the third state \(s_3\) can be computed as:

$$ s_3 = update(t_2, update(t_1, s_1)). $$

We simply replaced \(s_2\) from the second formula in this section with the right term of the first equation.

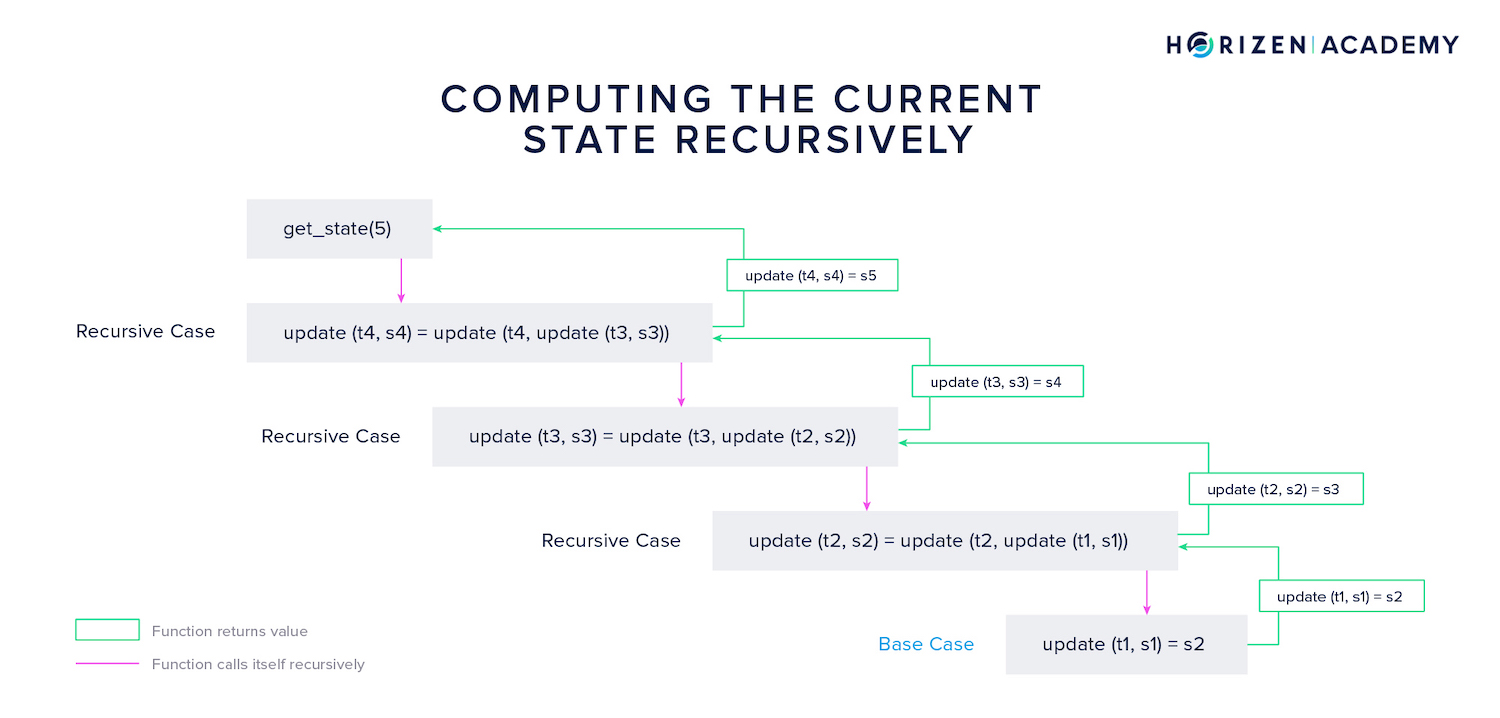

Recursive State Transition Proofs

The construction shown above follows the same pattern we discussed when calculating the factorial. Do you recognize the recursive pattern? The function update calls itself subsequently and opens new instances of the same function until the base case is reached.

The base case here is the first state transition resulting in state \(s_2\). Once this base case is reached, the different instances of the update function return their result to the next highest instance of the same function until finally, the current state is returned and all instances of the function are closed.

A general mathematical expression for this is

$$ s{n+1} = update(t{n}, s{n}) = update(t{n}, update (t{n-1}, s{n-1}) $$

This construction is of great value for verifiable sidechains. Not only can states be computed recursively, but so can proofs for each state and state transition. What is needed for the Zendoo protocol is a proof of the statement:

There was a series of state transitions \((t*1, ..., t_n)\) and by applying these state transitions to the initial state \(s_1\) one after another the state \((s{n+1}))\ is reached.

We now understand how to compute states recursively. But why do we want to compute a proof for each of those transitions? Remember that the mainchain does not monitor the different sidechains and verify the state transitions.

To avoid monitoring all of the sidechains, we can verify a proof submitted with each incoming withdrawal certificate. When validated, this proof will return true if the sidechain operated as intended, and false if it didn't. The mainchain accepts backward transfers included in a withdrawal certificate if, and only if the attached proof evaluates to true.

Using SNARKS - Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge

So how does generating a proof work exactly for a given sidechain? First, there exists a wide range of proof systems.

The proof system used for the Zendoo sidechain construction is a SNARK proof system - an acronym for Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge. Let's dive deeper:

- Succinct refers to the proofs being "short" in the sense of computationally inexpensive to generate and verify.

- Non-interactive means that the prover and verifier don't have to be online at the same time. With non-interactive proofs, the prover can construct the proof without the need for communication with the verifier. This proof can be recorded on the blockchain to be verified at any time.

- Arguments of Knowledge describes the proof being computationally sound, i.e. no adversary can construct a false proof even with access to huge computational resources.

With SNARKs we can produce proofs of constant size for almost any type of computation.

A SNARK proving system comprises a triplet of algorithms: Setup, Prove, and Verify.

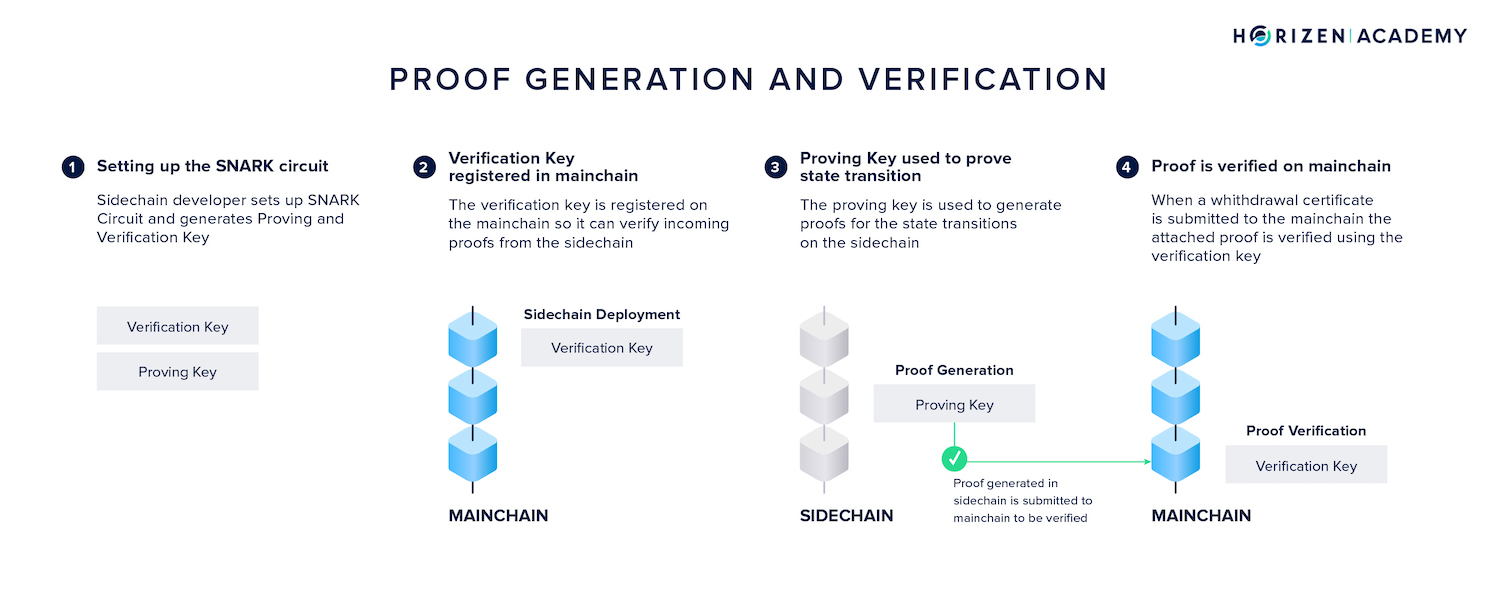

When a SNARK system is setup, a proving key \(pk\) and a verification key \(vk\) are generated for the system C. The verification key is registered on the mainchain at the time of sidechain deployment.

$$ (pk, vk) \leftarrow Setup(C) $$

To prove a computation was performed correctly (or, in more general terms, a statement) a proof \(\pi\) is generated. Generating a proof for the correct state transition \(t\) from state \(s_1\) to the final state \(s_n\) happens based on four inputs:

- the proving key \(pk\)

- the initial state \(s_1\)

- the transition \(t\)

- and the resulting state \(s_n\)

$$ \pi \leftarrow Prove(pk, (s_1, s_n), t) $$

Just like we computed states recursively, we can compute proofs recursively.

The logic is exactly the same: Starting from a base case (the first state transition) proofs are sequentially merged until a single proof for the state in question remains.

This proof is now broadcast on the mainchain where it is verified. Verifying a proof of state n \(s_n\) happens based on four inputs:

- the verification key \(vk\)

- the initial state \(s_1\)

- the final state \(s_n\)

- and the proof \(\pi\)

$$ true/false \leftarrow Verify(vk, (s_1, s_n), \pi) $$

Proofs for the correct execution of the sidechain logic are generated periodically, one for every withdrawal epoch.

Only the proof and the final state have to be transmitted to the main blockchain.

The initial state can be taken from the bootstrapping transaction or the most recent withdrawal certificate. The verification key resides on the mainchain since deployment. It's important to note that proof generation doesn't have to happen in a trustless environment. A sidechain might just as well use a Proof of Authority scheme where a group of trusted certifiers generates proofs.

Now that there is a basic understanding of what proof systems are, how recursion works, and how it is applied to generate proofs for any state (block) of the sidechain and in turn all withdrawals, we continue by looking at the remaining modifications to the mainchain needed to enable sidechains.

SNARK Usage in Latus Sidechain

It is ultimately up to a sidechain developer to decide how proofs of state transitions are constructed. In Horizen's reference sidechain implementation, the Latus sidechain, proofs are first generated for individual transactions. These proofs are then merged pairwise to get a proof for the entire block. Another sidechain implementation might merge them sequentially like in the example used above. The developer can choose their preferred method.

Once a withdrawal epoch has ended, the proofs for all blocks contained in that epoch are merged. This yields a proof of the entire epoch and all transactions within it. This withdrawal epoch proof is used to generate a final proof attached to the epoch's withdrawal certificate. This final proof legitimizes all backward transfers to the mainchain, proves all mainchain blocks were referenced, and all forward transfers were included.

The entire process of key and proof generation, as well as proof verification, is quite sophisticated. Some mechanisms described herein are simplified to convey the concept to a wider audience.

Sidechains Transactions Commitment

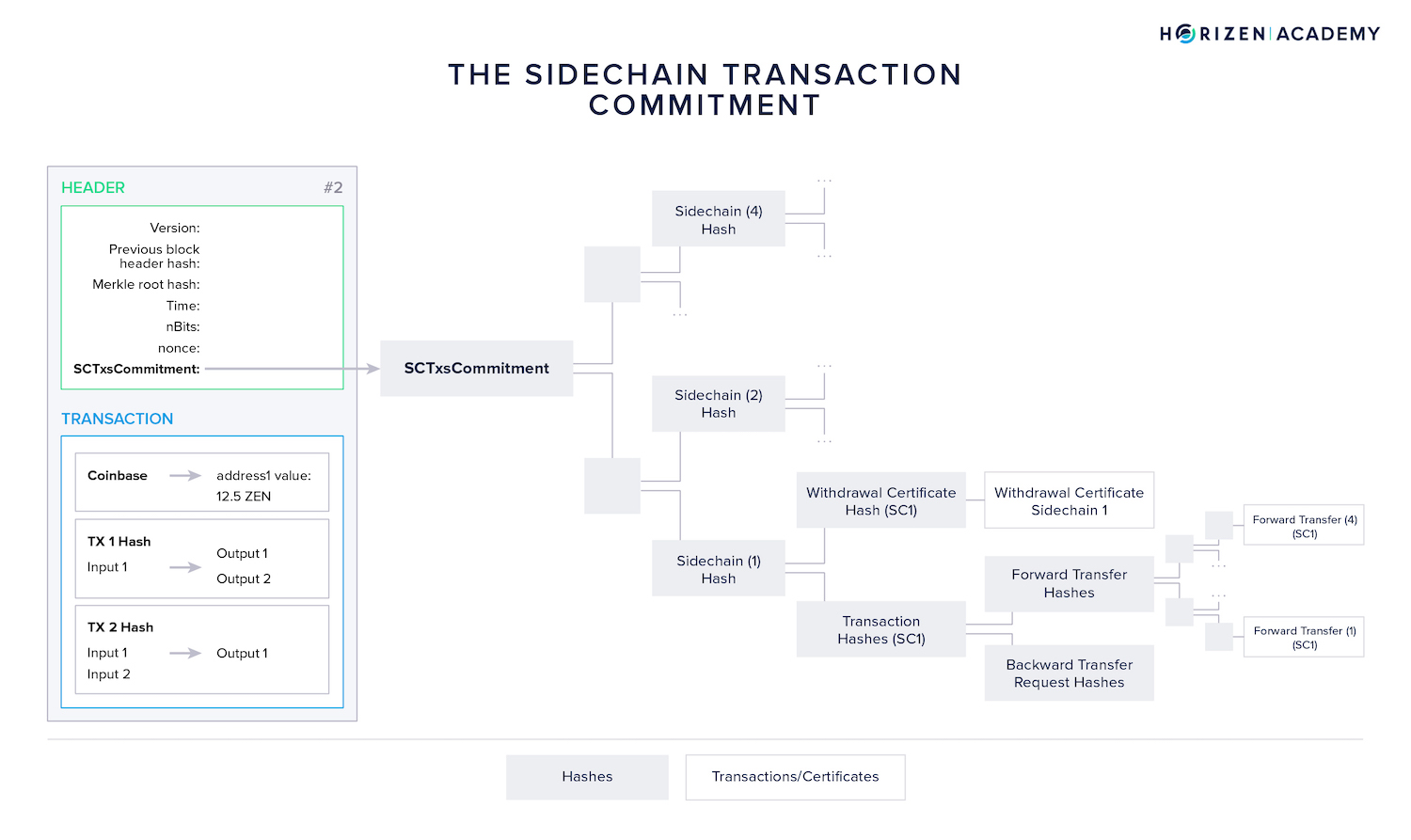

The structure of the mainchain block headers was upgraded and a new data field, the Sidechain Transactions Commitment (SCTxsCommitment) was introduced. The SCTxsCommitment is basically a Merkle root of an additional Merkle tree.

Besides the regular Merkle root included in a block header serving as a summary of all transactions, this second Merkle tree comprises all sidechain-related transactions, namely:

- Forward Transfers (FTs) sending assets from main- to sidechain

- Withdrawal Certificates (WCerts) communicating Backward Transfers to the mainchain

- Backward Transfer Requests (BTRs) initiating Backward Transfers from within the mainchain

- Ceased Sidechain Withdrawals (CSW) allowing a user to withdraw assets from a sidechain which has become inactive

All these sidechain-related events are placed into a Merkle tree, grouped by sidechain identifiers into different branches. The resulting Merkle tree root is placed in the mainchain block header as the sidechain transactions commitment.

Including this data in the block header allows sidechain nodes to easily synchronize and verify sidechain related transactions (sidechains DO monitor the mainchain) without the need to transmit the enti4re mainchain block. Furthermore, it allows the construction of a SNARK, proving that all sidechain-related transactions of a given mainchain block have been processed correctly.

Withdrawal Safeguard

Uncontrolled inflation of the monetary supply is one of the most devastating bugs a blockchain can suffer from. One has to consider an event where a malfunctioning sidechain is trying to transfer more assets to the mainchain than it initially received. This could be malicious intent or simply an honest mistake.

Horizen implemented a withdrawal safeguard to prevent this. The mainchain keeps track of how much money was transferred to a given sidechain, and will only accept incoming backward transfers up to that amount. This way uncontrolled inflation becomes impossible.

Sidechain Deployment

A new sidechain in Zendoo needs to register with the mainchain using a special type of transaction called a bootstrapping transaction. Any user can build a new sidechain and submit a bootstrapping transaction wherein several essential parameters are defined.

- First, a unique identifier, the

ledgerIdfor the sidechain is defined in the bootstrapping transaction. - Next, it is defined from which mainchain block onward the sidechain will become active.

A number of cryptographic keys are proclaimed for each sidechain, namely the verification keys needed to verify proofs generated on the sidechain. There is a verification key \(vk*{WCert}\) for withdrawal certificate proofs, a verification key \(vk*{BTR}\) for Backward Transfer Request proofs and a verification key \(vk_{CSW}\) for Ceased Sidechain Withdrawal proofs.

Lastly, it is defined how the proof data will be provided from the sidechain to the mainchain (number and types of included data elements).

Summary - Zendoo

Several sidechain implementations exist, some of them closer to production than others. A common shortcoming is that these constructions oftentimes either rely on the mainchain keeping track of sidechains, or they require some sort of certifiers to process backward transfers from side to mainchain. The Zendoo protocol allows an asymmetric sidechain construction where the mainchain doesn’t monitor sidechains but can rely on objectively verifiable proofs to validate Backward Transfers.

Zendoo comprises three main elements: The mainchain consensus protocol, the sidechain consensus protocol for which the Latus reference implementation is provided, and the cross-chain transfer protocol.

MCP and CCTP are fixed, while there are many degrees of freedom with regards to the SCP.

Next, we looked at the necessary modifications to Horizen’s mainchain protocol that allow the deployment of sidechains. To understand the recursive proof system that allows the verification of backward transfers without certifiers, we introduced proof systems in general. We showed how recursion could be used to elegantly solve mathematical problems such as computing the factorial of a number and how the same concept is useful for computing state transitions and proofs.

Another modification to the mainchain is the addition of the sidechain transactions commitment (SCTxsCommitment) serving as a summary of all sidechain related transactions on the mainchain in the form of a Merkle tree. The withdrawal safeguard protects against unintended inflation originating from a buggy or malicious sidechain.

Lastly, a special type of bootstrapping transaction is introduced to allow the permissionless deployment of a sidechain.